Idealog - January 2007

Capsule Culture 1

31.01.07

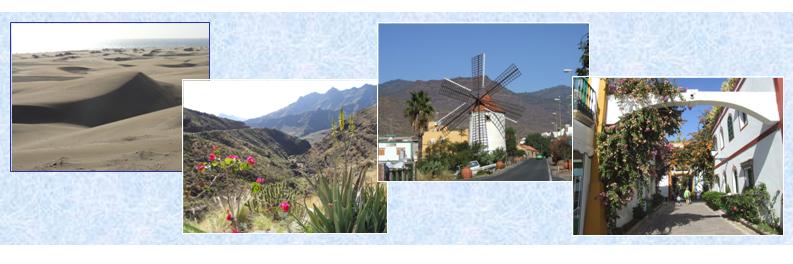

Staying in a hotel in Masapolomas on Gran Canaria while visiting placement students, it became clear just how many visitors actually visit very little. The hotel was large, well equipped and with pleasant, helpful staff. All meals could be taken in the attractively-designed restaurant - guests with yellow wrist bands were 'all-in', others like me were on half board. There were other restaurants nearby, the better ones a longish walk or short taxi ride away. On the other hand the hotel restaurant had a wide selection of food and congenial company so it was easy to stay indoors. There was a good bar, an entertainment area (same performers in different costume each night) plus swimming pools and sun beds. It was quite easy to avoid or take part in anything you wanted. There were even four or five shops with entrances from the hotel as well as the street.

We had heard from friends and relatives that Gran Canaria was a great place: we would enjoy it. People in the hotel - people who we got on well with and shared experiences as people do - said the same thing. Some had been coming for years. Then we found out that hardly any of them had been more than a street or two away and sometimes not even that.

When there's a reason to go further and a hire car with which to do it, there's a motivation to get out and about. Drive on the wrong side of the road? Just takes a short while to get used to. After a few attempts to negotiate the streets in third gear (that pesky gear stick isn't where I expect it to be) it gets easier. And once out in the country or the mountains the roads are quieter (but they don't half twist and turn and disappear into tunnels frequently. That's when you realise you forgot to find out how to put dipped headlights on).

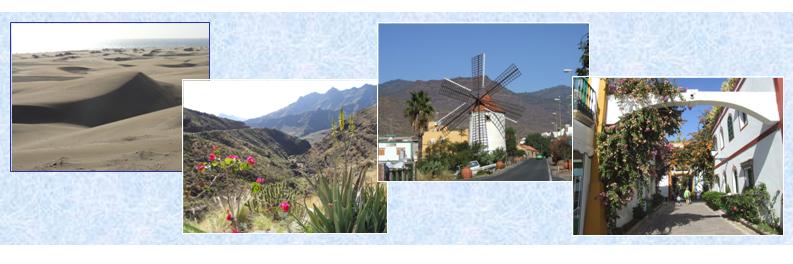

So getting out and about lets you see the amazing sand dunes a mile or so from the hotel, the windmill near Mogan, the rugged mountains near San Nicolas, the pretty houses (all tourist accommodation, too) in Puerto Mogan). There's a restaurant on the harbour there that does a proper paella as well as other local food. Up in the mountains is a roadside shop where the friendly owner offers samples of cake and wine and explains in excellent English where they are from and what is in them. What nice people!

A holiday in a resort hotel is relaxing and entertaining and fun: getting out and about a bit is even better. Escaping from the capsule culture of aircraft, bus and hotel is what tourism should be about.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Seaside Style

30.01.07

There are a number of books about seaside architecture. Some are local in character and others wider in scope. Lynn Pearson's book came out in 1991 and uses a title applied in Victorian Britain to exhibition and concert halls such as the one in Glasgow which still thrives. She covers a range of buildings including on-the-pier theatres, early cinemas and entertainment complexes like Winter Gardens (steel and glass structures containing trees and plants which sheltered visitors in the winter). There is a gazetteer of pleasure buildings erected between 1870 and 1914.

Fred Gray's book is more recent - 2006 - and is an extensive survey illustrated with old photos and newer ones from many sources and often in colour. While it is largely about Britain it also includes examples from the USA to Australia.

Gray, F (2006) Designing the Seaside: Architecture, Society and Nature, London, Reaktion Books

336pp

257x212mm

ISBN 10: 1 86189 274 8

£29.00

Pearson, Lynn F (1991) The People's Palaces: Britain's Seaside Pleasure Buildings, Buckingham, Barracuda Books

112pp

262x212mm

ISBN 0 86023 455 X

£16.95

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Poble Espanyol

29.01.07

Tucked away in the streets of Palma, Mallorca, is a Spanish village. Not surprising, you might say, because this is Spain. This village is not just a Mallorcan place, nor is it 'just' any Spanish village: it is a blend of all of them.

In the 1960s General Franco, then Dictator of Spain (which since his death in 1975 has again been a monarchy) decreed that there ought to be an addition to the tourist attractions of Palma - a showcase of the architecture of Spain in miniature. It would show a collection of buildings representing the variety and contrasts exisiting in the country. General Franco thought it would be good to show visitors to Mallorca what other parts of Spain were like. You might call it a museum or a theme park, but in fact it is neither. Theme Parks have rides and funfair entertainment - this has neither. Museums preserve original objects - these has none of them. Poble Espanyol ('Spanish Village' in Catalan, the language of the area - Pueblo Espanol in Spanish) is a tightly-grouped set of replicas of regional architecture; but often not of complete buildings. Some structures have one side representing the style of one region while the other face is designed in the characteristic fashion of a different region.

The result is eclectic and a little confusing, but fun. It takes time to explore all the nooks and crannies and to see what lies around each corner. The problem is that in jamming them all together in a small area without any of the surrounding landscape being represented makes it tricky for the visitor to separate the buildings from each other. There are other 'Pueblos Espanol', notably one in Barcelona which was built for the International Expo of 1929. As perhaps the smallest this one is probably least well known, but it must have fulfilled its purpose to some kind of degree in showing off what else Spain had to offer regarding contrasting village styles.

The open air museums which started in the late nineteenth century, most notably with Skansen in Stockholm of 1891 are larger, more spacious versions. They generally have complete and separate buildings with some kind of appropriate landscape aroud them. Some, like Greenfield Village in America, do have buildings moved from very diverse locations in the USA to locations in the museum containing a heterogenous mix of styles. The Welsh Folk Museum at St Fagans near Cardiff is another example, although better spacing has reduced the problem. But all of them exist as showcases of folk culture to delight and educate the visitor.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

The Drama of Architecture and Religion

28 January 2007

Palma's Cathedral dates back to 1300AD but took some three hundred years to build. Then in 1851 it was damaged by an earthquake and rebuilt, and in the early twentieth century its interior was remodelled by the famous Catalan architect Antoni Gaudi. His work in Barcelona is now highly attractive to tourists and those visiting this dramatic attraction in Mallorca can see his style at work.

Like all medieval cathedrals this one stands prominently where it could act as a landmark to travellers as well as a relgious symbol. Indeed, it is easier to see its shape from a distance than when climbing the steps to it between the high walls of the town. Outside it is solid and massive, though its columns, buttresses and pinnacles break up the bulky form with heavenward-pointing lines. Inside it is darker, more sombre. Paintings, statues and stained glass windows draw the eye, aided by carefully placed lighting. On a January visit, on a Monday afternoon, there were few visitors so the cathedral kept its sense of awe.

Palma is a place of government, the arts and tourism. Its plentiful shops within the rabbit-warren of the old town and the adjacent later, broader streets are full of fashionable clothes and accessories. Tourists who go there will find lots of retail therapy as part of their holiday package. Those who go into the cathedral can add to that an appreciation of the spiritual force that has driven the people of the Balearic Islands and Catalonia.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Tourism as Theatre

27.01.07

All of the hotels in the photos above can be found along the waterside in Palma, Mallorca. All of them have balconies.

It's common in the Mediterranean to find houses with balconies. Older ones tend to be enclosed, squared-off versions of north European oriel windows. Larger houses within the Mediterranean area might have flat, open spaces on top of a ground floor room or on top of the house itself. These were pleasant spaces during the heat of the night or the fresh cool of the early morning where people could take their ease. In many places stone-built dwellings might have quite plain sides and rear but very ornate, beautifully-carved balconies with balustrades and ornamentation, the 'face' of the house presented to the outside world.

British visitors flocking to the high-rise resorts of the Med love their hotel rooms with balconies looking out over the sea. How disappointing if the balcony pokes out onto a side street or some back yard! The balcony has even made its way back home, following in the path made by chianti bottles in little baskets with a candle stuck in the top, or straw sombreros and toy donkeys. Those perfectly misnamed "executive apartments" springing up in every corner might well have juliette balconies - rather like French windows which slide back to reveal not an attractive space for a couple of chairs and a table but a set of horizontal bars that stop you going anywhere.

Tourist-hotel balconies seem to have three uses. The first is to give space to continue sunbathing when away from the beach. The second is to supply private, secure space where the users might still feel 'out there'. The third use is that of a private box at the theatre.

If you can choose your hotel well and make sure you get a room with a view, the balcony is like a box in La Scala Milan or the Paris Opera. Away from the crowds of fellow tourists traipsing past your bit of beach, these elevated viewpoints offer all day entertainment coupled with domestic comforts a few metres away. What makes it better is the view of what is happening in front of you.

Our tourist staggers out of bed in a morning .. OK, leaps like a gazelle .. and the first duty is to report on the weather. In the summer, in Palma, Mallorca, it will be hot and dry as like as not, but in the winter coolness, even rain, is possible. Next, what is happening in this bright, leisure-time world? Well, a lot of townspeople are almost certainly off to work and to be pitied by the holiday-making tourist. The hotels in the photographs look out across a busy road towards the marina straight in front, the city centre and fishing harbour to the left and main port over to the right. Ferries are coming and going or just being loaded ready for a voyage later in the day. Tug and pilot boats are moving up and down to serve the shipping. In the winter, like this last week, few of the pleasure craft are unbuttoned and occupied by salt water sailors, but a few might be on the move. May be some have their owners aboard pretending to be sons of the sea, even though they might not know a bacardi from a bowline. I still treasure the memory of a power boat trying to leave its pontoon mooring in Port Solent, Portsmouth, without untying the main mooring rope. It nearly took all its neighbours for a trip to the Isle of Wight.

This is theatre at its best - a huge stage full of action building to a climax during Act 1, to be followed by drama and comedy as the subsequent Acts and Scenes unfold. The lighting effects are spectacular as the sun rises and clouds roll across with brilliant golds replacing the purple and blues of early dawn. A distant rain shower falls harmlessly on the water in the distance like a small, dark forest drifting across the plain. Even a thunderstorm can be a special treat for an audience safely on land and able to retreat behind sliding glass doors. Lightning flashes, cracks of thunder, driving rain and wind can come and go in one corner while comparative calm reigns at the other end of the field of view. As it drifts away, the sunshine spreading again across the town and its harbour so does life emerge again, people returning to whatever they were doing in a fresher, rain-washed world. Small dramas of family and community life unfold. Members of the species Homo Phonus walk by in deep, one sided conversations. Children splash through rapidly-drying puddles - with no beach just here they have a duty to get wet by other means. Dogs appear, taking their owners for walks: the Mallorcans love their dogs as much as the British do and parade them up and down in bright little coats or park them alongside while their owners drink cafe solo with friends they haven't seen for at least two hours.

Shakespeare, my boy, you might have known that all the world's a stage, but you can't have known how your little globe would turn one day into theatre on this scale.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Experiential Learning - Edgar Dale

20.01.07

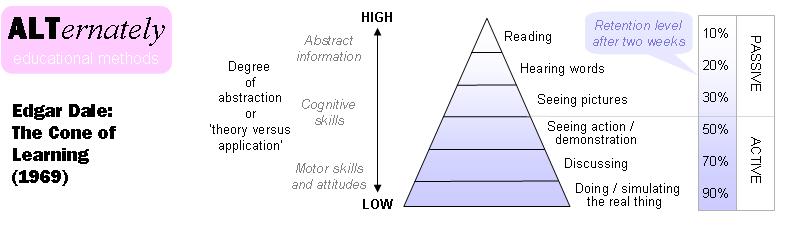

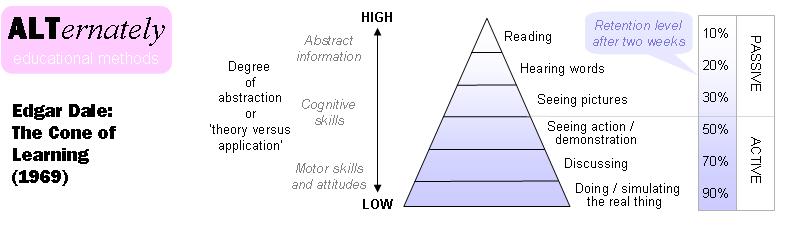

Edgar Dale's well-quoted 'Cone of Learning' or 'Cone of Experience' was first published by him in 1946 but is often related to work in the 1960s and a book on audio-visual methods of 1969. Numerous publications, presentations and web sites refer to the Dale concept and make much of the percentage figures he included as to the effectiveness of different communication channels. It is not within the scope of this posting to argue the validity of these figures, but many researchers would now say that that they are too neat and generalised to be truly accurate. They don't allow for variations, in the quality and effectiveness of the text, pictures, demonstrations or participatory activities referred to, or in the learning approaches of the user of these media. However, there is much to suggest that Dale was broadly correct and that as indicative descriptions of effectiveness his 'cone' is a useful model. Like many other authors I have used a two-dimensional triangle with internal divisions rather the cone that he described. His concept has also been illustrated using a pyramid shape. Educationalists have made frequent use of Dale's ideas.

The development of ideas in Experiential Learning is often traced back to Dale although it can be seen in much earlier writing and practice. To be slightly flippant, note Wackford Squeer's dictum to Nicholas Nickleby that the best way to learn about horses was to have the pupils of Dotheboys Hall clean out the stables.

Experiential learning occurs in travelling and the discovery of destinations and what they contain. Tourists read interpetation panels and captions in museums and art galleries, but probably retain only a part of the written text - and observation would often suggest they don't read all of a long caption anyway. An accompanying illustration makes the communication, and therefore the learning or discovery of something more effective. For that reason I try to illustrate these postings attractively and often, and I do the same in my lectures using PowerPoint and data projectors. A visitor watching a demonstration of craftwork will absorb or retain much more than they would by reading rather abstract text and still pictures, at least in my own experience as a viewer and as a teacher. Doing something, taking part in something, is best of all: riding a railway, sailing a boat, having a go at throwing a pot or gathering leaves on a Sri Lankan tea plantation: then you know how hard and back-breaking some of these things just are.

It also helps to explain why students on placement learn such an enormous amount from spending time doing a job: a year doing it is even better.

Dale, E (1946) Audio-Visual Methods in Technology, New York, Holt, Rinehart and Winston

Dale, E (1969) Audio-Visual Methods in Teaching, New York, The Dryden Press

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Advance To Go

19.01.07

In the 17 January posting I referred to visiting students on placement. There were five, scattered throughout hotels in the Canary Islands. Leeds Met Tourism Management students don't only spend their placement year in hotels, but a wide range of tourism activities such as local government departments, tourist attractions, tour operators, online booking agencies, transport operators and others.

I asked the five in what way would they come back different? I was talking to two of them together but the others individually. All of them came back after only minimal thought with the same answer - that they would be more mature and have more confidence. Each of them said they would be able to deal with other people better, that they knew they could work in a team and so on. One of them said what I have heard before - that she would know something about the pressures management are under when she got to a management position some time. One said she would have a better idea how to treat staff properly, having seen good management (and occasionally, bad) in action. One young lady said she had learnt a great deal from watching a particularly good manager at work. She could watch him for hours, she said. Well, I think she was talking about his ability to be charming to the customers.

They all felt they understood people from different countries better and were more sure of themselves when dealing with those visitors. Oddly, two students - who I know had never met - made the same comment about tourists from one particular European country (and it wasn't Britain, funnily enough) who couldn't understand why some hotel employees couldn't speak their particular language. In that strange way that the British used to have, those visitors would speak more slowly and louder in their own language, appearing to think that it would make the bewildered staff member awrae of what they were saying. They got very up tight if shouting made no difference. On the other hand, said one of these students, Swedish visitors would ask where they were from and then talk in that staff person's own language - so long as the Swedish visitors spoke it themselves, and they seemed to speak several languages.

On our university course we stress that the placement is where you can learn by doing, and even make a few mistakes with, hopefully, only minor consequences. Those mistakes become learning situations in educational terms. Gaining work experience, seeing new places and meeting new people - and learning by actually doing - are some of the reasons for doing the 48-week placement.

These days, with pressures on the time spent in education where tuition fees have to be paid, there are temptations to try to fast-track and to miss out the placement year. Its like missing out a Gap Year if you do that, and those years have become very popular. Experience gained and money earned is the reason for both gap and placement years - well worth doing while you can.

I tell students that they can save one year by fast-tracking, but they will then lose three: a year spent gaining maturity; a year gathering experience to strengthen the rest of the academic course on return to university, and finally a whole year in a professional job to go on a CV or resume. They will have a flying start over those people who didn't do placement, and its quite common that good placement students will be offered permanent positions at the ned of their course should they be interested.

My five students seen last week would agree with the vast majority of our ex-students - that the placement year will turn out to be one of the best features of their management degree years.

(In the photos above: four other ex-students who found great value in doing a placement). __________________________________________________________________________________________________

The Sights of London - British Transport Films

18.01.07

Originally appeared on westwood232.blogspot.com on 7 July 2007

British Transport Films was set up during the period of the postwar Labour Government which brought all kinds of key industries under national ownership. It also created special units within these industrial organisations or as sub-departments of government. The BTF was one such. Its remit was to produce films to instruct staff, inform the public, and promote the services offered by publicly-owned transport operations.

One such was that of special trains for schools' use. The German children of the 1890s mentioned in the previous posting used railways. In Capital Visit: A School Journey a group of 55 ten-year olds plus staff from Headless Cross Junior School in Redditch are shown making a two or three day visit (it isn't quite clear which) to the capital in 1955. The contrast between the two kinds of visit is noticeable. In this film it is the children who tell the story and give many opinions on what they see and feel. The German children were not allowed to pronounce private opinions. On the other hand it appears these children had everything organised for them. They were not formed in to committees to lead, follow up or identify points of interest not on the official schedule. Both groups used railways, stayed in hotels and took part in a variety of visits. The Worcestershire children went to the Science Museum, the Tower of London; made a boat trip on the Thames, saw Runnymede of Magna Carta fame and toured Heathrow Airport and St Paul's Cathedral.

The film might have been made some sixty years after the excursion undertaken by the German group, but it appears just as far distant in time from our day, too. This was the London of soot-blackened buildings, still with bomb-damage, before 1960s Paternoster Square buildings began to stifle the surroundings of St Paul's. It was still a time of National Military Service, and the boys in the group are heard giving their ideas of which service they wanted to enter. So there is militarism in this film, too, especially in the scenes of Changing the Guard at Buckingham Palace and a view of marching cadets at the Tower of London. Interestingly, though, these boys would not be called on to do National Service as it would be abolished before they had reached the age of 18.

The fashions were different. The children - generally slimmer in face and figure than today's ten-year olds - are more formally dressed, small versions of their parents, wearing smart coats, the girls in shapeless berets and the boys in school caps and ties. They stay in a hotel which has varnished wood on the lower half of its walls and fading flowered wallpaper (probably varnished, too) above. The light switches are old fashioned, ugly little lumps stuck on the wall. They still have tomato ketchup on the breakfast table (label turned away in this non-commercial film production) and the tea comes from an urn.

As a picture of a tourist trip it's a gem. Steam railways, cramped, single-decker buses - the red double-deckers do spin by on the streets which are relatively traffic-free. On the river they take a launch not all that different from those of today. But what about Heathrow!! Staff who appear to be a pilot and an air stewardess (well, that's what they were called) walk them airside between Viscounts and Ambassadors and Constellations (proper aircraft with propellors) which they can touch. One boy runs his fingers along the edge of a propeller and then wipes them on his jacket. In those days children were less worldly-wise without much television to show them everything before they went near to a plane or a palace. On the other hand they could go where today's kids cannot go, behind the scenes and beyond the barriers. In so many cases today children can only visit at second-hand by looking at a TV or computer screen.

The film shows a school visit and what it entailed in a way, and with an immediacy, that we just have not got when trying to observe a school visit like that of the young Germans over half a century before. We can see something of the character of the teachers but hear none of their thoughts. We see delightful pictures of the class members and a little of their own characters. But there is a jarring dissonance which opens up a gap between us and them and makes us suspicious - no, it reminds us - that a film, however good, is the work of a producer, director, camera operator and sound recordist. The film was shot silent. The sound was recorded at Beaconsfield Studios using a boy and a girl to give voice-overs, reading a carefully-judged script written by an adult. And the accents are south eastern, middle class, and terribly well spoken - probably by a couple of ever-so nice children from the BBC.

It strikes such a false note. Kids from Redditch? This pair would give anyone the needle.

Capital Visit: A School Journey is one of twelve films made by British Transport Films between 1952 and 1966 on a double DVD album from the British Film Institute and called See Britain By Train. Highly recommended for nostalgic views of the time, but also as documents illustrating the life and times of postwar inland tourism. There are now three in the series and others made by different producers.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Vive El Gleichartigkeit

17.01.07

Which title is sort-of-eurospeak for "long live similarity".

When I was in school geography lessons were usually about different peoples with different ways of life in places different from my own. A good thing, too. The world was full of things I would not recognise and would probably have thought Pretty Suspicious. There were burning deserts and frozen ice caps, boa constrictors, coconut palms and people who said "clarse" when I said "class". These things were not to be found round my Staffordshire home, but nonetheless they were part of life's rich pattern even if some of them were to be avoided like the plague.

It was generally good to be taught the world possessed diversity. In the late 'forties and 'fifties the second world war had been won. Britain had lost an empire but gained a commonwealth, which in 1953 at the present Queen's coronation supplied hundreds of colourful troops and personalities to process around the nation's capital. The cinema, radio (and later TV), books, magazines and newspapers celebrated these events repeatedly. Much later I was to realise, more or less along with everyone else, that being top dog meant that Britain could easily fall into the trap of dismissing other peoples' ways of life as inferior. They were not like us and so were wrong. Primitive. Dodgy. Different.

Going abroad was therefore probably unnecessary and was likely to lead to being corrupted. The food was bad, they were dangerous drivers, they lacked a sense of humour, communication was difficult (they failed to speak English and flapped their arms about) and as for their politics - well, it was all aimed at replacing the natural British leadership of humanity and that was something to be prevented at all costs. Travel was expensive, took time and form-filling to plan, even longer to get anywhere by ship or train and could only be tolerated if little British colonies were established where warm beer, fish and chips and cups of tea like mother used to make were readily available and we could then spend the rest of the day turning the colour of lobsters on the nearest stretch of beach.

It's good to observe when travelling abroad these days that much of this has gone. Low cost airlines, TV reporting, substantial immigration and a more open-minded younger generation have worked a few wonders. There is still plenty of prejudice about - some rude remarks on Big Brother and the odd race riot or three shows that. On the other hand the teens-to-twenties age group has been abroad much more, is much more likely to have lived near, studied or worked with people of European, American, Asian and African origin and to have laughed their socks off at non-white sitcoms and skecth shows on TV.

Many more students have taken that famous gap year finding themselves in distant destinations from Acapulco to Zanzibar. Many will have done a placement year abroad. Others will have volunteered to work for a time in communities which have much to offer as well as many needs to be fulfilled.

I have just spent a few days visiting tourism management placement students abroad. Travelling around is quicker, cheaper and easier than ever, and while that might be stacking up some concerns about global warming it is also contributing to world peace and understanding. International tourism is usually managed through the use of the old imperial language, English. While that has an effect of eroding the use of other languages and cultures it has a great advantage: having a common form of communication helps us understand each other quickly. Old perceptions about struggles to comprehend each other are fading away. We like foreign food and can't get enough of it. Sport, spectacle and music in its many forms help us share cultural life even if we don't know enough of the spoken language. None of this should be made an excuse to forget about learning languages or, indeed, for destroying other cultures in the name of making them easy for tourists to enjoy.

I wonder, therefore, whether it more important to teach our children that other folks are really just like us - same needs, same hopes and fears and the same desire to know and support each other.

Fifty years ago my geography teacher showed a film about life in an African village. In those days we learned to appreciate that it was different and why it was different. Nowadays we can learn that those people are 95% like us and it is that percentage of them that counts.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Children's Holiday Homes

15.01.07

Originally appeared on westwood232.blogspot.com on 5 July 06

The kind of social conditions produced by the industrial cities of the nineteenth century started a number of initiatives to get children into the countryside. These often started as day excursions organised by Sunday Schools attached to churches and chapels. Those schools started by teaching the theory - that a better life would exist beyond the daily grind of farm and factory, but indeed, beyond the grave. Then they moved on to show that in practice a taste of a better life was available more immediately in the form of a trip to the coast or countryside. Funds were raised and transport organised, at first in the shape of horse-drawn wagons, later the railways being built around the nation. Thomas Cook's 1841 excursion from Leicester to Loughborough was one of these, though run on commercial lines. A verse in The Lady's Home Magazine of around 1904 encouraged readers to give ninepence (in 'old money' quite a donation) to give "some poor child a happy day".

The new Local Authorities set up to improve the life in towns and cities around the mid nineteenth century had to take on the role of providing education to all children within their boundaries. Many of them cooperated with local charities to run residential holidays of a week or more, often in buildings converted from other uses or specially designed. A Manchester and Salford Children's Mission operated a centre at St Anne's on the Lancashire coast.

Boys from Halifax could go to a tented camp near Filey, and later both boys and girls could spend a fortnight much nearer to home at Norland Moor, away from the smoke of the town. These were generally children from less-well off homes. The system still operated in the 1970s, and the building stands with its gold-painted lettering announcing itself, as seen in the photo.

Wakefield children could go to a camp on the Holderness coast near Mappleton. That village housed a whole range of camps. One was owned by the Young Men's Christian Association. During the war it was used by the army, then afterwards took in boys from the north east as part of the British Boys For British Farms scheme. Groups in Hull had camps at Great Cowden and Rolston. Under a later arrangement the West Riding of Yorkshire sent children to the Rolston camp. The Bradford Cinderella Society ran one at Hest Bank, though it was at one time controversial as being said to be run by "an aggressive atheist".

Leeds children can still use a Holiday Camp at Silverdale on the edge of Morecambe Bay. It was founded by the Leeds Poor Children's Holiday Camp Association in 1904. On its recent centenary a history of the camp was published in celebration, and a BBC web site has collected many memories of different kinds from people who attended as chidren. A purpose-built new building was opened in 1952, replacing one which had been erected in 1920 after the original was destroyed by fire. The new one has a swimming pool with high-diving boards.

The type of holiday enjoyed by children to these centres has generally been based on the place itself with activities and games taking place within them. They have used their localities to greater or lesser extents as the organisers felt fit. In that, they were just like other holiday centres, bases for fun and games rather than exploration of regions in the way field study centres would become. Which is just what most people on holiday want.

McNeil, F (2004) Now I Am A Swimmer: Silverdale Holiday Camp, The First Hundred Years, Leeds, Pavan Press

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Representations of Reality

14.01.07

Originally appeared on westwood232.blogspot.com on 4 July 06

Here is shown life in the 1820s, a time when Britain was largely an agricultural country, many people lived in sturdy cottages and travel was by stage coach. Handsome horses had not yet been replaced by steam trains and cheery tollhouse keepers helped keep the turnpike roads in good order. Prosperity was reaching out to the world.

Except that many of those statements did not apply to large parts of the population, who might work in coal mines, live in hovels and never travel other than by foot, and possibly no further than the next village.

You are reading a selection of words chosen by me about some features of life in the 1820s that I have selected to write about. You are looking at a photo whose subject appears to be something about the 1820s. The photo shows a view chosen to frame a tollhouse, stagecoach, cottage, and a film camera operator. It was taken in the mid 1970s and so some elements - the camera, the man's hair style - are of that era. And actually, the tollhouse keeper waving to the coachman has a 1970s haircut. So not only is my message here selective, so is the photo. It's worth pointing out that the clarity and colours of what you can see are the product of the camera that took the original transparency, some possible fading through thirty years, the accuracy and setting of the scanner that produced the computer file, and the software that was used to enhance the picture a little. Even the image is the outcome of selection and processing.

The filming was for a BBC programme about stagecoaches. A preserved vehicle was brought in with a team of horses and people in costume as driver, guard and passengers. The stagecoach and horses' appearance and actions might or might not truly represent such a team as operated in the 1820s. Might there be some tiny differences of materials used or methods of driving?

The tollhouse was built for the Holyhead Road at Shelton outside Shrewsbury. In the photo it can be seen against a hillside covered in trees - it was removed from what in the 1970s had become a busy A5 and was re-erected at the Blists Hill Open Air Museum, part of the Ironbridge Gorge Museum. The Museum contains a number of remains - such as former iron-smelting blast furnaces a few metres away from this scene - which are 'native' to the site and therefore authentic; plus others like the tollhouse which have been rebuilt here to save them from possible destruction elsewhere. There are yet others built out of materials scavenged from various places in order to show what domestic and working life would have been like at some particular time.

Whether the scenes created are authentic, or indeed, representative of the chosen time and place depends both on the viewpoint of the curators, rebuilders and presenters. That 'tollhouse keeper' was a museum employee whose job it was to interpret to the visitor the life of the time in that cottage. So he kept the house as if he lived there (which he didn't) with a coal fire in the grate, a garden with growing vegetables and a sty with pigs. And a couple of hens running round.

The Museum guide book had its own words and pictures chosen by other staff. Ove the years new editions replaced old, the basic message staying the same but with subtle changes to the contents and possibly the colour and glossiness of the printing.

Is it a scene of progress, busy-ness and a British community thrusting forward with its industrial revolution, contributing to a new world of prosperity and hope? Or one of political propaganda, of nationalistic, defiant nostalgia in the face of a British decline post-empire, post-war and post-industrialisation? Are tourists being attracted in to the Museum as part of its educational aims and objectives, selling them tickets and souvenirs in order to sustain the high costs of running such an enterprise? Or are they being relieved of their money to keep a few old fogies able to play at their games of empire?

As you read this piece and study the photograph, keep in mind why it was taken, what the cameraman was doing and why the stagecoach was running; and then why the three-dimensional bit of theatre in this Museum had been built, its interpreting staff recruited and trained and its guidebooks designed. And keep in mind, too, that at every step what we think is happening and why, and whether it is 'authentic' or not, depends entirely on our own opinions and motivations.

That's history, and that's tourism.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Launching Children's Adventure Tourism

13.01.07

Originally appeared on westwood232.blogspot.com on 3 July 06

The author of Swallows and Amazons, Picts and Martyrs and other children's sailing adventure books is buried in Rusland churchyard in the Lake District. Ransome reported on the Russian Revolution for the then Manchester Guardian and got to know Lenin and Trotsky. His second wife was Evgenia Shelepin, who served for a time as Trotsky's secretary. They lived in Low Ludderburn in Cumbria, and it was there that he wrote his books. Arthur Ransome was born in Leeds. His family - his father was a Professor of History at the University of Leeds - holidayed in a village at the southern end of Coniston when he was a boy. While Ransome was by no means the only writer of books based on everyday children's adventures, he effectively founded a tourism industry by popularising sailing in small boats, linking the activity with adventuring in a way, unlike works such as Treasure Island, that children could really do themselves. His series of books based on the Walker and Blackett children have been in print ever since and have a powerful following worldwide. All the places that he wrote about can be traced even though he blended some from different locations and gave romantic names to many. The children themselves were partly modelled on real acquaintances whose characters were often drawn into the figures in the books.

Photograph: Arthur and Evgenia Ransome's grave in Rusland, Cumbria.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

The Wrong Kind of Tourists

12.01.07

Originally appeared on westwood232.blogspot.com on 2 July 06

Invaders are not tourists. At least, the military type are not. Thirty years ago this year, however, Turner and Ash wrote a book using the phrase The Golden Hordes to refer to what was then 209 million international tourists each year, evoking the image of Ghengis Khan's destructive armies. Of the more modem variety of military of whom there are large numbers carrying out the role for which they were trained at this moment, we know that the taste of travel that they enjoy often leads to more peaceful journeying. I wrote about one example in an earlier blog.

What about business travellers? No - I don't mean they might be invading armies, though some people think so. Are they tourists? It's an interesting question because discussions of tourism tend to be about leisure travellers, especially when critics choose to adopt a rather Calvinist approach to what they seem to think is a sinful, hedonist pastime, that kind of thing. Of course, they never indulge themselves in such trivial pursuits - their travel is for Serious Reasons. So how should city centre hotels be classified when they earn most money from Monday-to-Friday business people, useful income from weekend leisure guests, and some very nice earnings from local people using their bars and restaurants? And, of course, many business visitors use the same infrastructure as everyone else and might well pop in to an attraction or two, especially if accompanied by a partner not on business.

One of the arguments being put forward on this web site is that leisure travellers are also explorers and, if you like, students of the world and its activities. A fortnight in Benidorm or San Antonio can be a real education, nudge nudge, wink wink - remember why the young milords were keen to go on the Grand Tour? Be that as it may, it's difficult being dismissive of leisure travel when the experiences prove so influential. So on the one hand there are clear motivations for travelling but they are not always as clear-cut as we might believe from a superficial look.

A useful way to look at travel is that it is based on four reasons for going, and that these need to be considered with a degree of flexibility. They might also all be involved in some form or other in any single journey:

Exploration: either as the first humans in a particular location, or the first of one group of people to encounter another group; or as any individual going someplace that he or she has not been before

Conquest: which might be military eg Iraq; or religious, eg Mormon evangelists abroad

Business: travel in connection with an occupation (and sales people are also engaged in a version of conquest)

Tourism: defined here as travelling for leisure. A tourist might, therefore, spend some time exploring, doing business, and even perhaps in a small, culturally-based way, conquering. Some national tourism offices try to encourage certain kinds of visitors who they hope will alter the culture of a destination by their more sociable behaviour or philosophical outlook. There are examples in several mass-tourism areas where service standards are low, and where it is hoped a more demanding visitor will stimulate change.

Now, those Vikings were certainly travellers: which of the above definitions applied to them?

Turner, L & Ash, J (1976) The Golden Hordes: International Tourism and the Pleasure Periphery, New York, St Martins Press

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Outdoor Education in Germany

11.01.07

Originally posted on westwood232.blogspot.com on 6 July 06

The use of educational excursions and residential expeditions was introduced much earlier, and on a systematic basis, than other European countries. Most schools organised such visits every year with the use of day trips to historic or geographically important locations frequent - sometimes weekly. This was particularly so in the gymnasia which were intended as university preparation schools. The philosophic approach was termed Heimathskunde, the observation of local phenomena. As early as 1844 a book was published which was based on the walks taken by a teacher with his pupils.

The object of the visits was to instruct children in a love of their homeland, its history and culture, and how it related to the wider world of Europe and beyond. As history was taught by the 1890s in three stages - the study of heroes, the study of states (mainly Germany) and the study of the world at large, it was considered essential to give illustrations to the stories which teaching employed by seeing actual places. Geography was required to do similar things, demonstrating the natural landscape, the historic landscape, and the human activity from farming to industry which the German peoples had developed. So visits were made to mountain tops to see the views, to farmlands and villages, and to towns and cities with the industry within them. Residential journeys of two weeks' duration using the railway and hiking were common - often an annual event.

Some schools set up their one-day excursions as great occasions in which the whole school and its teachers marched forth behind a school band, with parents and others to watch them go. The youngest children at the rear walked the shortest distances before stopping for educational activities. Older children walked or marched further. At the end of the day they returned behind the band, forming up again as the more junior classes were brought back in to the procession.

The University of Jena ran its own gymnasium as a training unit for student teachers. Its longer expeditions brought together the older children together with trainee teachers from the university and the school teachers. Complicated journeys of two weeks length were made, for example through Bavaria and the Thuringian Forest, using long train journeys to get there and a mix of shorter rail journeys, hikes and mountain climbs to reach each location. Castles, historic villages, the homes of famous Germans such as Martin Luther, and factories making glassware and porcelain were featured. On one occasion they arrived at the Schloss-Altenstein, home of the Duke of Meiningen. The teachers in charge had heard the Duke was at the castle and they expected to be refused access to the grounds, but as they approached the grounds the Duke appeared, taking his morning walk. He stopped and chatted to the teachers, looked at the notebooks used by each child, and then led them to the balcony of the palace in order to get a better view. Then he summoned a soldier on duty and had him conduct the party round the estate. In other places local workers were invited to describe places and activities to the party, which an observer reported they did with great competence.

The teaching was definitely a matter of instruction, followed by questioning which was often responded to by the whole group in chorus. It was not expected that any child would venture an opinion or ask a question: it was not part of the educational method. In preparation for visits the group had learnt songs, often patriotic, and these were used to add to the sense of place and to revive weary children after a day walking. They stopped overnight in hotels. Small groups of children took it in turn to lead the way, bring up the rear, look out for points of interest not listed in the itinerary, and finally to help organise the domestic arrangements.

Out of this system came a number of things. Perhaps one was the powerful sense of highly organised patriotism which fuelled German attitudes to its position in the world of the first half of the twentieth century. It also, however, produced some of the great pioneers of geography like Humboldt and Ritter. Third, it fostered the huge love which German people have today of touring the places of the world and which makes them some of the most prolific travellers - and travellers with a purpose, which is to explore and to discover.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Baedeker Guidebooks

10.01.07

The intense interest in geography amongst German people has a long tradition, as the next posting will also illustrate. Much modern theory in the subject can be traced back to men like Humboldt and Ritter who explored and reported on their extensive world travels.

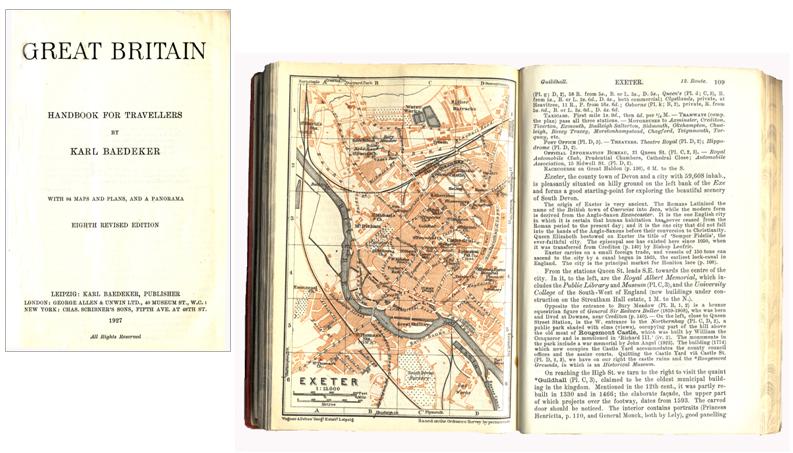

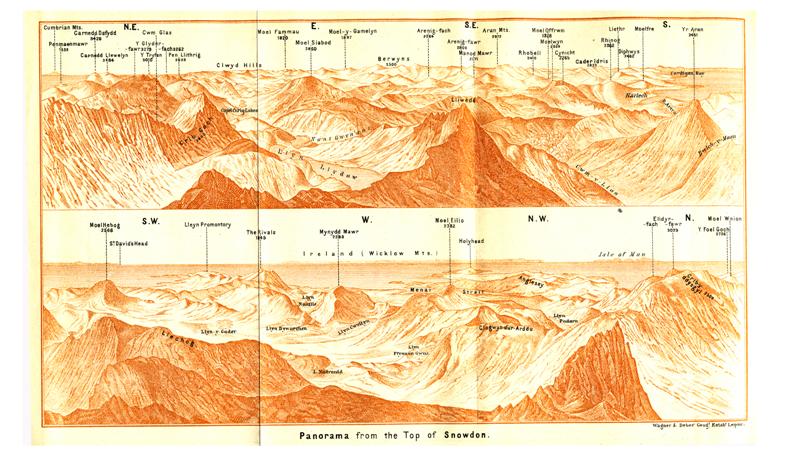

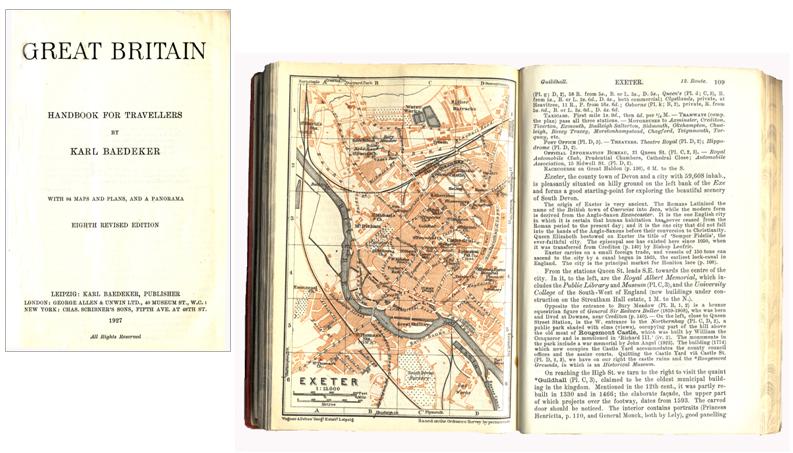

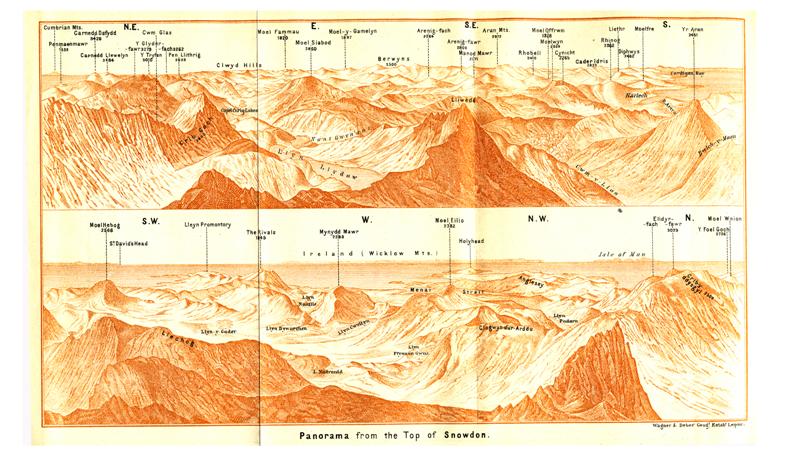

Karl Baedeker contributed in a different way. Having set up a printing business in Koblenz in 1827 he reprinted a guidebook to the River Rhine and followed it by publishing one of his own. From the success of that guidebook he began the business which became world famous for highly accurate, well illustrated guide books.

The label "Baedeker" became well known enough for travellers venturing overseas to use it generically - in place of the term 'guidebook', in fact. Karl Baedeker had from the beginning employed specialists to research the detailed information he thought travellers required, and included beautifull, accurate maps on thin, fold-out sheets glued in to the books as they were being bound. The topographic view of North Wales was one example. In some mountainous areas - such as the Lake District of Britain - markers had been placed on viewing points to help visitors name landscape features. These guidebooks included some of their own - a step towards armchair travelling for those who could not make journeys themselves, perhaps.

The accurate details given by Baedeker books had a negative side. During the second world war it is said that Hitler told the Luftwaffe to bomb cities chosen from the Great Britain volumes. All places given three stars for historic importance were to be hit. This was in response to Allied air raids on Lubeck. Exeter was the first to be bombed.

The Baedeker Company's premises, and all of its archives, were themselves destroyed in December 1943 in a raid on Leipzig to which it had relocated in 1872. In 1949 the business was restarted in Freiburg and Baedeker guides are published still today.

(Illustrations from the 1927 guide: author's collection).

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

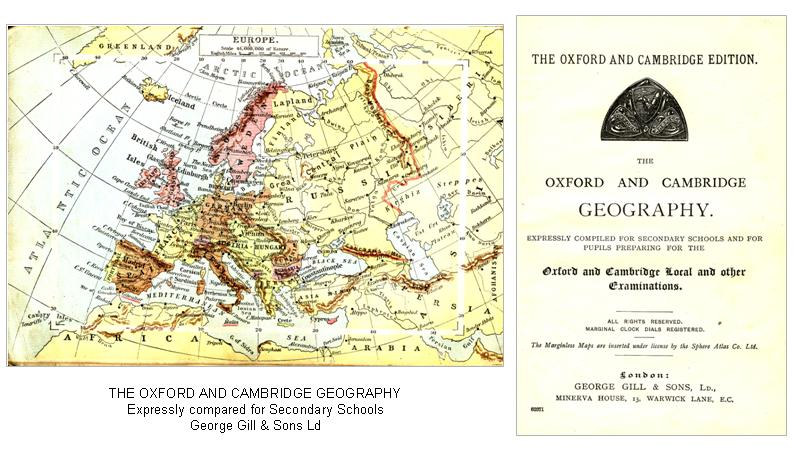

Laying Foundations - A Geography Text Book of c1901

09.01.07

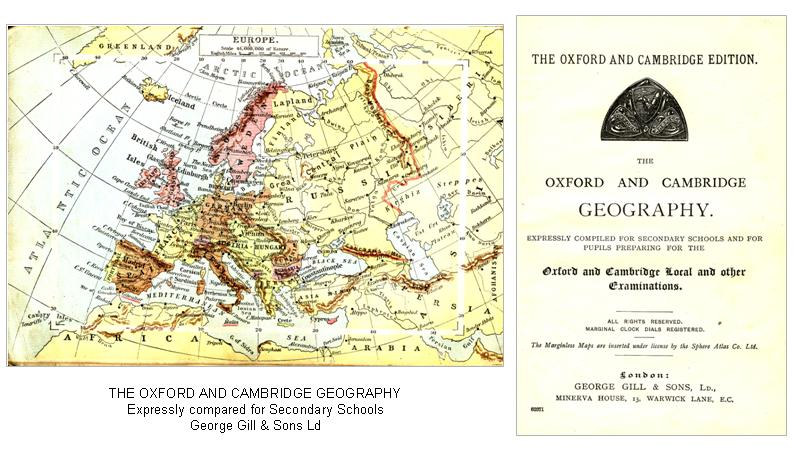

A century later than the question-and-answer geography book came this one aimed at preparing pupils for examinations. Gone are the questions and answers in favour of statements set out in a mix of typefaces. These were intended to show systematically the most important facts in each sentence. Coloured maps have been introduced.

The maps are fascinating pieces of history. Europe is shown with long-gone countries such as Austria-Hungary, a much more extensive Germany and Ireland undivided but part of Great Britain.

Africa had been carved up between imperial powers around the world, especially Britain, Germany, France and Belgium, with some independent states. The pink colouring of British possessions ran almost from the Cape of Good Hope to Cairo - but German East Africa stood in the way.

Like the 1801 book there is a map explaining the main geographical terms. The emphasis is on describing countries and their chief towns, and on economic production.

This copy of Gill's Geography still has the name of a relative written in the front from when she was at school before the first World War - when these same, competing imperial powers fought each other.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

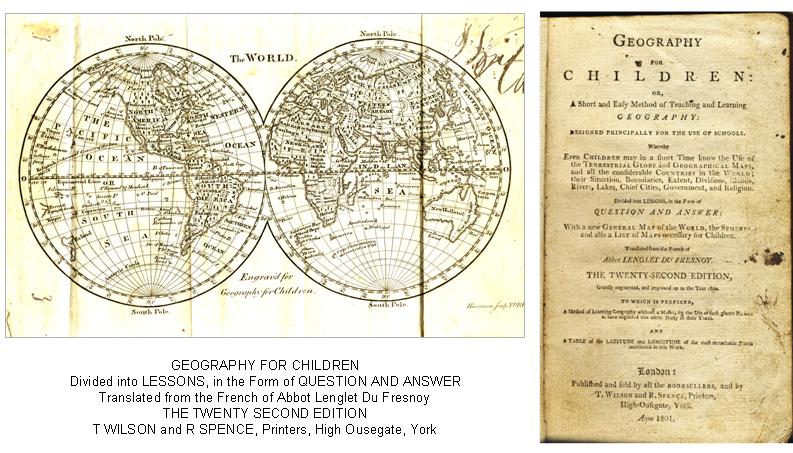

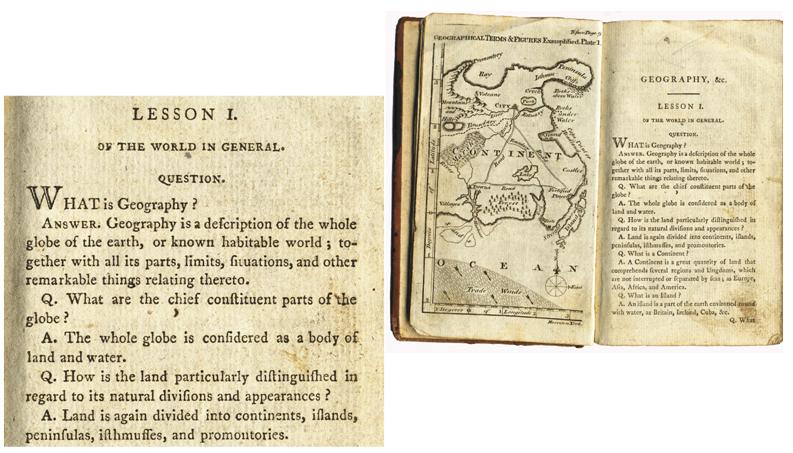

Laying Foundations - A Geography Book of 1801

08.01.07

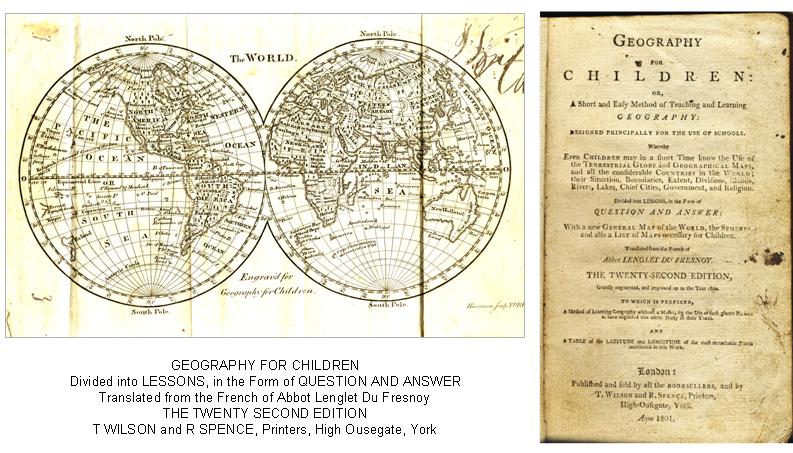

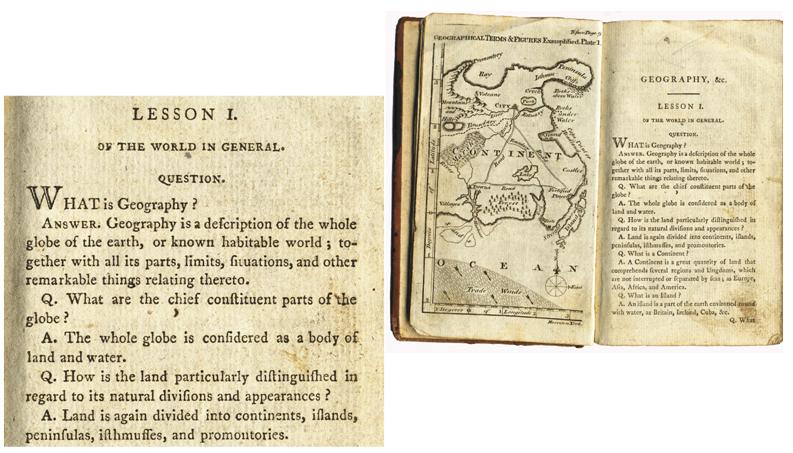

Earlier postings have drawn attention to 18th century novels and journals which have inspired travel. This is the first of a few examples from my own collection of a geography school book. In 1801 this kind of book was what set the formal foundation for many children of their world knowledge, perhaps alongside travellers' tales.

To devotees of Patrick O'Brien's Aubrey/Maturin maritime adventures set in the Napoleonic Wars period it is tempting to think an earlier edition of this book might have been what Jack Aubrey's tutor had used to introduce him to global affairs. It might be a little ironic to note it was written originally by a French Abbot.

The book was printed in York but primarily put on sale in London, according to the title page.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Drama Out Of Doors

07.01.07

The simple drama staged in churches and manor houses in the middle ages in Britain soon moved out of doors. Mystery Plays with a religious theme were sometimes performed on specially-made, horse-drawn stages on wheels. Other drama eveolved out of entertainments put on in the courtyards of coaching inns. The George Inn (left picture) in Southwark, London, was an example. It dates back to at least 1542. What survives is only part of the original, in which galleries overlooked a central area used as a performance space - open to the rain but at least sheltered from the wind. Audiences could stand in the yard or along the galleries around it. The George is now owned by the National Trust, but leased out to a pub operator.

Shakespeare's Globe has gone, but the near-replica dreamed of by Sam Wanamaker has been built close by and now sees dramas enacted again. There are other modern versions of the Globe around the world. In the middle photo is seen one that stands in an entertainment park in Prague, close to an exhibition hall, a theatre, a planetarium and a water-ballet theatre with hundreds of fountains and platforms between ornamental pools.

On the right is the famous Minack Theatre built by Rowena Cade between 1932 and her death in 1983. Cade was a costume designer and became much more besides. Local entertainment being limited in the 1920s, an amateur dramatics group was a welcome activity. A performance of "A Midsummer Night's Dream" was held in a field just in from the coast near Porthcurno Bay in 1929. From that small start Rowena began to create a theatre on land she had bought and used to build a house. Minack - Cornish for 'a rocky place' - grew over fifty years under her leadership into a world-famous stage - and a tourist attraction, just like the George Inn, the rebuilt Globe and the Prague version of Shakespeare's theatre.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

The Sealed Knot at Kenilworth Castle

06.01.07

The Big Bang Theory. The spectacular part of a historic re-enactment such as that of this English Civil War group is firing the cannon - and it was, to the audience at least, a very big bang. Letting rip with the muskets adds more fireworks until every sense is drawn in to the scene, even to a suspicion that you can taste the gunpowder on your lips - and you can't get engagement of all five senses in the cinema, no matter how techie they have got. Being there calls on every sensation and then some, as you're in the middle of it all and can do your own bit of interaction from giving an involuntary shout as the shock wave hits you, to asking a question of the people acting out the supporting roles - doing the cooking and washing or preparing the armoury.

When could you last do that in the cinema or in front of the telly? __________________________________________________________________________________________________

Influences on Travel - Romany

05.01.07

"Daddy, was anyone interested in nature before Mr Attenborough started on the telly?".

Well, dear, quite a few. A man from Yorkshire called Cherry Kearton made films for the cinema about wild life abroad in the 1920s, and Armand and Michaela Denis made many from the 1930s onwards. They were very popular on TV in the 'fifties and 'sixties. Then there was Jacques Cousteau who made underwater films of wild life - they were famous. He had his own ocean-going research ship called the 'Calypso' - it was converted from a Maltese ferry. But there was a really famous man on the radio in Britain just before the war who isn't well known now, but should be .....

The Reverend George Bramwell Evens was a Methodist Church minister who had looked after churches in Carlisle and Huddersfield before going to King Cross Methodist Church in Halifax. The church is still there but has just closed this very month.

Evens had a Romany mother who was born in a vardo, the Roma name for a horse-drawn caravan. He had a huge interest and knowledge about the countryside and supported the ativities of the Scout troop formed at the church. He would often drive to their camp site in Luddenden Dean and entertain them with stories sat around the camp fire with his dog, Raq, sat by his side.

In 1932 Evens was asked by a producer for the BBC in Manchester, Olive Schill, to lead a radio programme about the countryside. On 7 October 1932 the first broadcast took place. In those far-off days presenters were called Uncle someone or Aunt somebody (there was once an Auntie Cyclone. Think about it), but he didn't fancy being Uncle Bramwell - the name he was usually known by - and on the spur of the moment said he wanted to be known as Romany. A 1930s legend was born.

In the programmes Romany was heard taking walks through the countryside with two children, meeting people, and, of course, animals along the way. The programmes were amazingly successful, bringing the real atmosphere of the countryside into people's homes. Except that they were all studio recordings with sound effects.

"Walks With Romany" was what the broadcasts were called, and they encouraged many people to go for their own walks exploring the countryside.

The series continued into the war. Sadly, however, romany died in November 1943, and although another presenter, given the name 'Nomad' took over, the Bramwell Evens magic had gone. By that time Romany and his wife were living in Wilmslow, Cheshire, close to Manchester with the BBC studios on Oxford Road. They had a vardo. It now rests by the library in Wilmslow, and is open to visitors on certain days advertised by the library.

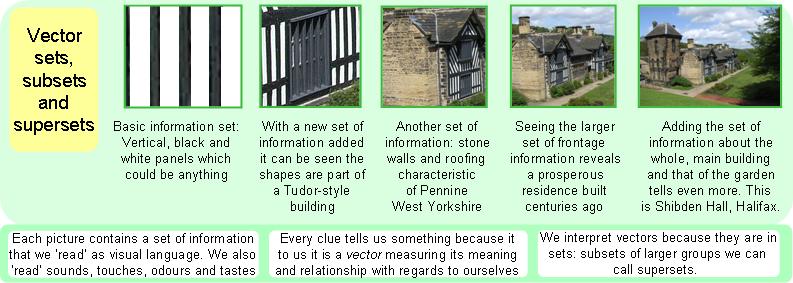

Towards Theory - Vector Sets

04.01.07

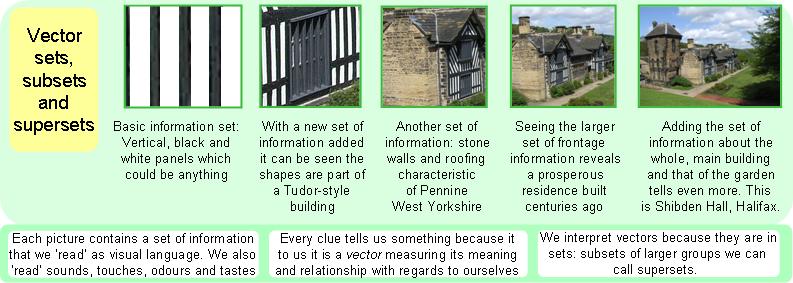

The suggestion being advanced in this group of postings is that all perceptions (or 'percepts') can be termed 'vectors' because they enable us to recognise certain features or qualities established in a definable, or measurable way.

Take a leaf, for example. Its colour might be called one vector; its texture another, its shape a third, its size a fourth, and so on. The set of vectors will tell us it is a leaf and not a blade of grass or a twig (or for that matter a person or building). It will also tell us that it is one sort of leaf - perhaps an oak leaf - and not another, and that it is seen it its spring or autumn colours as appropriate.

If we see the leaf as part of a group on a twig, perhaps with acorns, helping to confirm its nature as from an oak tree, not an elm, ash etc, we would be seeing the leaf as a set of vectors subordinate to a larger set - the twig/leaves/acorns set. The leaf is a subset of a larger group we can call a superset. Of course the twig/leaves/acorns set is also part of another superset - one further up the scale of magnitude, which we know of as an oak tree. the tree is probably part of a bigger group yet again which we call a wood. It is an infinite scale running upwards. Every group is part of a larger, superset, which is in turn a subset of an even larger superset.

In the example shown in the photos above, the basic information - the lowest order of subset - turns out to be part of a superest which consists of timberframe wall with windows within it built on a course of stonework. This group is actually a subset of one corner of a house - the next superset up the scale. That set is a subset of a house, which is in turn a subset of a residence in the setting of some grounds. The subset/superset relation could be continued higher up the scale to see it within a town park set within a valley which is within an area of Pennine hills - and so on.

It's important to recognise that sets are not fixed and are largely inventions in the mind of the observer, and they are even then only rather general concepts adopted by humans in order to understand and communicate. People use the term 'leaf' and know roughly what they mean, without having (or even attempting) to worry about an exact definition based on all of its parts. And yet people do need an understanding of what qualities make up the object known as a 'leaf'.

If a metalworker came along and reproduced a leaf of the exact shape, size and colouring of a leaf, but in metal, we would not be fooled into mistaking it for the real thing - there are several differences giving the show away - but we would appreciate that a craftsperson had produced a representation of one object by exchanging one or two basic properties - metal substituted for organic material with small changes in texture, feel etc.

In perceiving objects, we first of all tend to observe the overall features before looking closer and closer. The depth of our analysis depends not only on how much detail we need to know but on our knowledge and experience (and persistence). The building shown here is seen to be a late medieval building with later changes and additions (such as the Victorian tower). Specialists would examine the detail of the garden, trees and indeed the building itself in order to understand more and more of what is in the picture.

The visual example discussed here is based on only one of the five human senses. Were we stood in front of the house we would have the sounds of birds, the breeze in the trees, perhaps some people nearby; plus the feel of the warm sun, soft wind, springy truf or hard pavement; maybe a smell or two and in theory some taste - but as humans we ue those two much less. The dog we are taking for a walk would have a better idea (interpreted differently) about the range of odours and possibly a taste or two, but be less interested in the same sights and sounds that take our attention.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

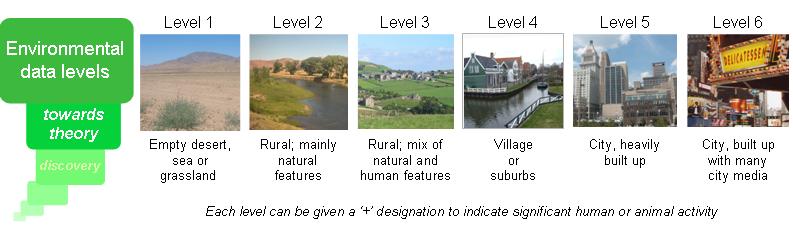

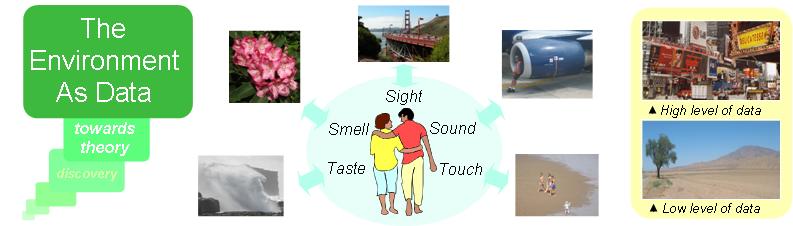

Towards Theory - Environmental Data Levels

03.01.06

It helps to understand peoples' reactions to places, and therefore to be able to provide useful services or management, to be aware that different environments represent different levels of data. It might be very difficult for someone used to open grassland country to cope in the big city. It's easy to understand the noise and sense of rushing and perhaps the claustrophobic effect of high buildings close together, but there is more to it than that. The brain is trying to process enormous amounts of information coming in through five sensory channels - sight, sound, touch, smell, taste - at high speed. The competition for attention of all these messages might mean that some get forgotten or ignored even though they are important. Warning lights might be missed and accidents caused. Expensive neon-sign or video adverts might be lost amongst the tidal wave of information sweeping over people. Planners have long known about the need for variety in townscape design and the introduction of soft landscaping like quiet, green parks. The communicators who work with cities have to know how to handle the noise and razzamataz and be able to draw on appropriate other media or quiet phases as well. Effective communication depends on knowing the audience's needs and people are not all the same: tour guides, teachers, advertisers and city managers all need to know what is best practice in communication. Yet poor road signage, ineffective advertising, wasted teaching time and inadequate tour guiding are all easy to find in every city.

The opposite can also be true. The big city resident gets out in the plains, the desert or close to the sea and finds nothing - literally, since they are used to entertainment and information being in their face and the apparent lack of interesting scenery is often a cause of disappointment. They need to look closer, differently, and to learn to appreciate that what seems to be emptiness is in fact a source of huge interest. The sweep and shading of desert dunes, the great contrast with cityscapes of open grassland, the movement and colouring of lakes and seas is a source of reward to those who understand. Within those places life and activity occurs on a different scale and in unfamiliar ways. Visitors need to look for it; local people can help them find it. It's a failure if visitors go away disappointed and unaware of what these places offer, and the destination manager might just possibly be the one to blame.

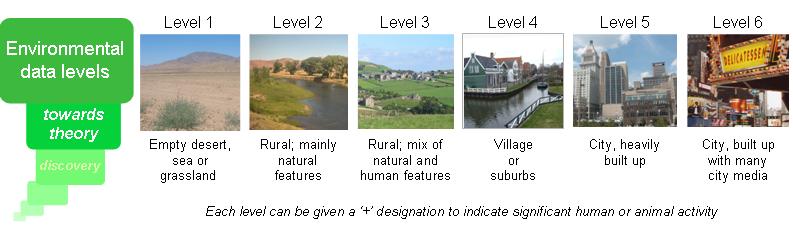

Illustrated are six examples of environments with varying levels of data of the kind these current postings are discussing. There aren't absolute boundaries separating one from another - variations from place to place and within places occur quickly; also, opinions will vary as to the amount of data to be found in each, not least because it partly depends on the knowledge and experience of both visitors and managers. In addition, changeable weather or storms add large amounts of activity to an otherwise quiet place, as do the activities of human beings or wild life. A downpour of rain in a desert might quickly bring fresh growth of plants and attract wildlife, bringing more action and increasing the flow of perceptions to the visitor's brain. A desert might be cosnidered at level 1 normally but temporary activity of these kinds, while not turning it into a permanent level 2, ought to be designated as different for a spell, so would be described as level 1+ for the duration. Really heavy activity might be termed level 1++. Similar designations could be given to the others as appropriate, though it would be less useful thinking of level 5 (city, heavily built up) and level 6 (the same with many townscape media features permanently on show - adverts, signals etc) because high rates of human activity are part of their normal character.

In summary, it is important to be familiar with what it is within different environments that make people react to them as they do. That helps managers and opinion formers to know more about the communications context of their work. From that they can plan more effective strategies.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Towards Theory - Environmental Vectors

02.01.07

Let's think of those people in the graphic below - the previous posting. A couple of visitors in a new place - an environment which is probably new to them. You know that feeling you sometimes get when you wake up in the morning: Where am I? What day is it? If you had a really confusing dream you might be thinking - Who am I?

Of course we generally know just who we are, though it might get a bit confusing when age takes its toll and young children might not be too sure sometimes. And what about those kinds of phases in the teenage years when people say they are really "discovering who they are"? There is something in our psychologies that suggests knowing who, when and where (let along how or why) isn't quite as automatic as we might think it is.

In our home environment (OK - when we are "at home") it is so familiar that we aren't conscious of any kind of orientation - having to work out where we are and why. And yet, if you closed your eyes, could you picture exactly what your kitchen looks like, down to the order of the utensils hanging from that rack? As we actually look at them we know what they are and are happy to see where they are, without needing to think any further. On going out of the house the chances are we will be able to walk quite a way before thinking that we don't recognise our surroundings. We might hop on a bus or get in a car and travel along quite familiar routes. Yet there almost certainly will be people we haven't met before, or well-known people dressed differently, or vehicles that we don't know. There will be little combinations of acitivities - patterns of movement of the people, the cars and lorries, even the animals passing by. What about the flowers that have opened, or the trees that changed colour? And how often do you see a sky that is exactly the same today as it was yesterday? - cloud formations are in constant motion.

That couple of tourists will almost certainly be in a very different environment from the one where they live - that's what tourism is about. So for them they are having to take notice of where they are, to understand something about it (such as - where are the shops? - the beach?) and then act according to their own needs and to what the place has. If they have a slightly deeper interest they might be working out something about what the place used to be like and why it has the particular form and culture that they are finding. Even if they only want shops, bar and beach and have no interest in history or culture, they will still register the differences in their surroundings, the people and the climate which was almost certainly one of the reasons they came there.

From the earliest times onwards, travellers have used landmarks. Prominent hills, buildings and even patterns of vegetation have helped them recognise where they are and work out which way to go. Robinson Crusoe described moving round his desert island, using the position of trees, the change to open grassland and the nearness to the sea. He learnt to use all of his senses, first to survive and then to make the most of his little world. Even taste was important in coming to terms with the island, for he had to try eating some of what was growing there in order to discover sources of food.

The most sophisticated travellers used small details from the landscape to help them. Sailors could ‘read’ the colour and shape of the waves around them to work out their position and know what weather might lie ahead. Land travellers might use information such as which of the side trees moss was growing to understand their position, especially when the sun was not visible. In similar fashion the modern traveller uses tiny details as well as major features of the surroundings to understand places.

To a tourist, the recognition of being in a different place is the most important thing. After that it is essential to know whether it is the right place for whatever they want to do, and if not, how can they get to where they want to be. They need to know whether they are going to be safe, to have available the food and drink they need, good accommodation and friendly people (just like Robinson Crusoe on his island). The tourist wants to know, in short, whether this is a good place to be, whether they will enjoy this particular destination. Some obvious, major features of the place will influence that, but ultimately there are probably hundreds, thousands, if not an infinite number of things which will have a bearing on it. An example: is there a good beach? Is it big or small, overcrowded or empty, clean or dirty, steep or gently sloping, a nice colour, made up of sharp or rounded sand grains, be well drained or to have standing water – even worse, quick-sand? That is only the beach: what about the nature of the sea? The weather? The area behind the beach – the tourist will want to buy goods, stay overnight, be entertained, have places to explore, perhaps some countryside as well as the town. A visitor interested in history will want to know where the older places are, just how old they are, what happened there, why they were built or formed as they were. Landmarks, and the smaller details that are often called ‘cues’, are not just to do with place, but with time as well. Beyond history they are to do with natural history and even geology. Connected with history and with the people who live in the place they are to do with culture, society, the way people live today and how they live.

In mathematics there is the idea of the ‘vector’, a quantity with direction and magnitude. I suggest that it is useful to think of people in a particular place as using vectors to work out how they understand, and therefore use, the place. They see a landmark, perhaps a temple on a hill at a certain distance away, and use it as part of the way in which they work out where they are: it is the Acropolis and that reminds them they are in Athens, in Greece and perhaps far from home. Of course they used previous cues to tell them they had arrived in Athens; the flight in, the view from the aircraft window and cabin announcement, then the drive from the airport during which they encountered an infinite number of cues which gave them an idea of place and when they arrived in the city centre. The smells and later the tastes of the city added abundantly to their knowledge, often taken in quite subconsciously. Part of the point here, however, is that they are constantly reminded that they are living at a particular time and that the Acropolis and all the other historic buildings represent very different times, when people did things differently from the way they are done now. Everything about the temples of the Acropolis shows that, reinforced and added to by the displays in the museums, the words of the guide books and the human guides who take visitors around. Every one of these details helps the traveller understand the relation of their place on the globe but also their place in history and their relation to the past. They also are able to relate to the natural history and present day human culture of the place as they receive information about those aspects of it.

An important point needs making here. A vector in this sense would not be the cue itself, but the perception of how something is different, and in what kind of way. It is a measure of magnitude and direction, although since those qualities depend on the phenomenon being perceived (shape, sound volume, texture, pungency, saltiness etc) then the vector is also a function of the phenomenon. It is indisoluably linked to it. When we work out the values represented by a vector we are then able to relate to it. In this sense, therefore, it is not the phenomenon observed, heard etc (the 'percept') that is the vector, but the difference of position spatially, temporily, physically and culturally between it and the observer.

A vector might then be any kind of perception at any kind of level: the brightness of the daylight, the colour of a stone, the smile on a face or the beauty of a butterfly. Not all of these perceptions are positives – the broken glass and scaffolding poles in the photo above give reference to a derelict building which speaks of economic change and perhaps a depressed community. What the visitor makes of what they taken in through their senses depends upon their interpretation of it which is in turn dependent on their own experience, knowledge and opinions. Each detail – each vector – is interpreted alongside all the others as it is placed in a wider context which builds over time. People establish their relationship with what they see, hear etc, by putting the perceived feature into the framework of their own knowledge. They measure its position and importance (“direction and magnitude”) in relation to themselves in the world. People are constantly receiving environmental data through all of their senses and interpreting it in order to survive, use and enjoy their worlds.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Towards Theory - Environment As Data

01.01.07

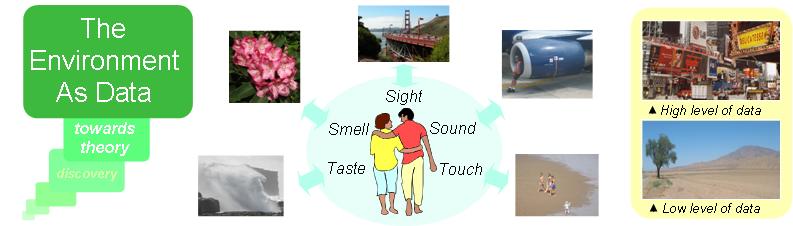

Anyone - doesn't have to be a tourist (or even a human being, come to that) - placed in a given environment will use five senses to relate to that environment. Some scientists will point to a probable sixth sense based on electrical signals - some fish have it; whether we do is not in my line of knowledge so that possibility will be omitted for the moment.

Vision is perhaps the most important sense to be used, hence the "Tourist Gaze" of John Urry (1990) mentioned in the previous posting on 31 December. We see a vast amount of detail very quickly and locate it relative to ourselves very easily, thanks to a wide arc of view and binocular vision. We can see attractive places, potential dangers, identify people with a high degree of perception about who they are and so on. Sight allows us to read their body language.

Tourist managers concentrate a lot of effort on manipulating our percpetions of their places, by making them attractive, keeping them well maintained and trying to ensure there are no hostile activities going on within them.

Sound is important. It's a bit more more difficult to locate its origins at times but it brings very rapid, strong perceptions which can be good, bad or neutral. Sound can range from a brief emanation from an otherwise inanimate object - such as the whistle of an approaching train - through longer-lasting patterns like the noise of the train as it arrives or the song of a bird. Or it could be a warning siren on a police car, or maybe the music played by a band parading. At its greatest complexity it can be in the form of spoken language of hugely varied character, according to the language used, mode of speech (face to face, by telephone or public announcement system).

Touch depends on ourselves and what we are doing. It is more a product of interactivity, or we might say, proactivity. Walking on a beach produces tactile sensations, themselves dependent on whether we have footware or not. The texture of stone, brickwork, grass, water, textiles, skin and fur depends on how contact is made (do we reach out or are we reached by something?). Interpersonal contact - shaking hands or exchanging kisses on meeting - tells us a huge amount about each other, and happens to bring in the possibility of smell and taste sensations. Tourism managers make prime use of sound from conversation to background music, or sound effects in an exhibition, or a whole panoply of sound in a stage performance.