The Environment As Data: Building New Theories For Tourism

Towards Theory: Typologies and travellers

16.12.06 (original posting date on alanmachinwork.net - Idealog)

Tourism has been defined in different ways since just before the second World War to the present (Holloway, 2006). These have ranged from the League of Nations definition of 1937 which talked about travellers spending at least 24 hours in a country other than their own up to that of the World Tourism Organisation, adopted by the United Nationas Statistical Commission in 1993, which reads:

"Tourism comprises the activities of persons travelling to and staying in places outside their usual environment for not more than one consecutive year for leisure, business or other purpose" (quoted in Holloway, 2006:6).

These are definitions of tourism. In more recent years the idea of purpose or motivation is introduced. This points towards ideas of a typology of the tourist, of which there have been several over almost forty years.

Eric Cohen (1972) wrote of a four-fold division:

1 The organised mass tourist who takes a package holiday to a popular destination

2 The individual mass tourist who buys a travel package which allows them more individual travel but still tends to stay within the popular tourist environment

3 The explorer who uses the comfort of hotels and quality tourist transport, but who then branches out to spend time amongst the host community

4 The drifter who travels and explores using whatever transport and accommodation they can find, avoiding the formal tourism industry.

Five years later, Stanley Plog (1977) used personality descriptions to classify tourists on a continuous scale, and linked this directly with destinations. At one end of the scale were the 'psychocentrics' who were less adventurous and inward-looking, and who chose well established resorts. At the other were the 'allocentrics' who were adventurous and willing to take risks in travelling and overnighting further away from the mass tourist services. In between the two most extreme examples of each of these were a range of variations on them, usually classified overall into five divisions with 'mid-centrics' half way along the scale. There were parallels in Plog's scale with Cohen's divisions.

Other typologies have been proposed, such as that of Smith in 1989 who included explorers, elite tourists, off-beat tourists, unusual tourists, incipient mass tourists, mass tourists and charter tourists. These labels are reasonably easy to decode as they also fit in with Cohen and Plog in describing a spectrum from those people who like to be organised and managed by others with little contact with the life of the destination outside their resort (Smith's charter tourists being the extreme) to the traveller who is often, and deliberately, not-a-tourist - Smith and Cohen's explorers, Plog's extreme allocentrics.

The problem with these kinds of typologies is that they relate largely to leisure travel and perhaps 'mainstream' business travel. There are many other forms of travel and all of them can be highly influential when it comes to finding out about the world, its people and its places. More attention is now paid to business travel as well as leisure travel, which is just as well since business travel is much older and has usually been much more important economically, at least in urban centres. Business travellers are not just people employed by companies and who are engaged in commerce, but those working in public sector and community affairs. Even this is rather limited a definition: what about the ordinary family shopper who makes an excursion to a city centre - perhaps staying overnight. Are they the same as a leisure visitor? If they are, is the difference with the business traveller a matter of individual as opposed to organisational motivations?

To understand tourism as education it is really necessary to take a step backwards. Tourism is still generally equated in the popular mind with leisure travel, even though as the WTO definition adopted in 1993 points out, it should relate to business "or other purposes". Just how broad should this "other purposes" be? Does it include soldiers invading another country?

It would be surprising if it were taken as such: a mechanised army is difficult to imagine as a party of tourists, much as some cynics might feel the effects are sometimes the same. Yet the recorded experiences of former military personnel show how influential their foreign excursions often were, especially if they spent some time away. It is often stated that only a small proportion of the citizens of the United States make leisure journeys to a foreign country. The importance therefore of the numbers of soldiers, sailors and air force personnel who have spent time in serving abroad becomes relatively greater in terms of shaping the perceptions of that country to non-American environments and cultures.

Other points might be made: when Cohen and Smith write about explorers as a distinctive group of people who travel independently and spend their time in studying new places, they miss the importance to even the mass traveller, or Smith's 'charter traveller', of their discoveries made, perhaps, incidentally to lying on the beach or dancing the night away. Even the most resort-bound tourist experiences, and remembers the hot, sunny weather day upon day (or occasionally the tropical storm or hurricane), the hotel employee of a different complexion, language or behaviour; perhaps some imported cultural entertainment, variation of food and architecture of the building. Most visitors will venture a little way from the hotel in most destinations, to experience local street scenes with their shops and people. These people are, in however small and haphazard a way, exploring.

Another point is that in cultural terms the visitors not only encounter and to some degree absorb new experiences, they bring them in turn to the host community. Historically, this helped produce the 'demonstration effect' by which local people were introduced to the culture and life style brought in by the visitor. Young people in particular often viewed the fashions, behaviour and accessories of the traveller with interest and perhaps envy, and then demanded that they be able to enjoy a similar kind of life style. Others presumably saw, considered, and rejected the ways of the foreigner in their midst and made haste to enphasise their own cultural norms. Some blend of these extremes was probably what usually occurred, changing in time in one direction or the other according to evolving circumstances.

It might even be important to consider other ways by which travellers have deliberately attempted to impose their own values and cultures. The soldier is one example. Another is the political or religious activist, ranging from the travelling evangelist in eighteenth century England, through to the Mormon of our own time; or the political campaigner during elections and the street demonstrators and political insurgents of the middle east. They are not tourists, but they use the same infrastructure, often spend many nights away and have at least as important an effect. These people are, in varying ways, often informally and in low-key fashion, engaged in conquest - the deliberate attempt to change other people's ways of life, politically, religiously, economically or culturally. It can be done by a rock group or a choir as well as by someone with a gun or a religious text.

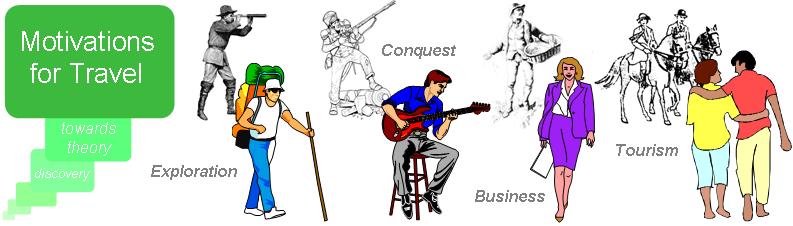

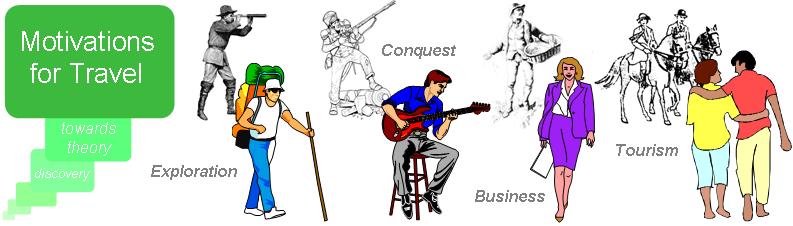

A suggestion, therefore, is to consider those people who travel away from their usual place of living as travellers, and that tourists be defined as those motivated by travelling for leisure purposes. The over-arching term travel then be subdivided in four travel motivations: exploration, conquest, business and leisure travel. The illustration above indicates that each took one form years ago and often a different one today. People almost certainly travel and are motivated by every one of the modern forms at some point or other in their travels. They also change with age and the accumulated experience of travelling, a point sometimes ommitted by the pigeon-holing classifications suggested by some commentators. Travellers might have to start as package tourists but can grow into seasoned individual veterans of the open road, seas and skies.

The ability and practice of humans being able to move around the globe is a complex, ever-developing phenomenon for individuals and communities alike.

Cohen, E (1972) Towards a Sociology of International Tourism, in 'Social Research' volume 39 pp64-82

Cohen, E (1979) A Phenomenology of Tourist Experience, in 'Sociology' volume 13 pp179-201

Holloway, C (2006) The Business of Tourism, 7th edtion, Harlow, Prentice Hall

Plog, S (1977) Why Destinations Rise and Fall in Popularity, in Kelly, E (ed) Domestic and International Tourism, Wellsbury, Ma, Institute of Certified Travel Agents

Smith, V (1989) Hosts and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism, 2nd ed, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Towards Theory - Writers on Landscape

[Originally posted here as an Idealog note on 31.12.06 ]

People have been trying to make sense of their surroundings forever. The first concern of early communities must have been for their immediate survival, with basic needs of food, drink, shelter and the availability of useful material resources. Later they would have longer-term, utilitarian, plans for future food and materials either extracted or grown as they learned the successful husbandry of the land. These concerns will have led them to explore for resources and to reconnoitre the land for its benefits and threats. Exploration had to lead to some kind of understanding, which would require some form of knowledge framework in its turn dependent on some kind, however, rudimentary, of philosophical perspective.

The writer on geography and anthropology, Yi-Fu Tuan (1974, 1977) examined ways in which peoples around the globe in both primitive and developed societies have tried to make sense of their surroundings. In Britain, W G Hoskins (1955) investigated the historical geography of England at around the same time that J B Jackson was doing the same for the American landscape. Their work followed in the tradition of other geographers who had, from the time of Humboldt and Ritter at the turn of the nineteenth century onwards been working out the principles by which the physical, natural and above all, human, patterns upon the Earth’s surface were related (see Holt-Jensen, 1999). Hoskins and Jackson studied human beings within local landscapes. Their approaches were similar, clear and accessible, not driven by a need to produce theories and paradigms for other academics, but explanations for the generally interested public. W G Hoskins was a well known broadcaster on his subject with a popular touch based on his ability to communicate. Environmental psychologists were developing theoretical ideas about people and places (Ittelson et al 1974, Lee 1976) which would have an important influence of landscape studies. Other geographers analysed the relationships between landscapes and societies further in the 1990s, such as Denis Cosgrove 1984, Gollege and Stimson 1997, Bryan Lawson 2001, Winchester, Kong and Dunn 2003: see also the collection of papers in Cosgrove and Daniels, 1998).

Cosgrove’s “Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape” (1984) examines the ways in which landscapes of Europe and North America have been perceived at different historical periods, mainly by opinion makers from artists and writers to political leaders. The depiction of places – landscapes, buildings, the events within the places – has a long and wide-ranging literature discussing numerous theories concerned with history, creativity and techniques. The phrase ‘reading the landscape’ has been used many times to describe how people perceive and interpret their surroundings. There is therefore a suggestion that the landscape is like a book to be read, a form of communication medium. John Urry has memorably drawn attention to what he terms “the tourist gaze” (Urry, 1990) of the visitor upon the place they have visited. He refers back to Daniel Boorstin’s (1964) argument that tourists want to see views of places, but are often presented with ‘pseudo-events’ or, in other, inauthentic views produced as part of a tourist industry. Urry reviews commentators like Barthes, Baudrillard and Bourdieu on such image-creation.

Recorded images are the production of artists and photographers. The designs that they produce can be studied in terms of visual language complete with a system of grammar. Kress and van Leeuwen (1996) are among a number of authors who have written on the subject. Architects have done so for much longer: Sir John Summerson’s “Classical Language of Architecture” (1980) details the work of the Greeks and Romans in terms of the ways in which their buildings deliberately communicated ideas of beauty and power to those who viewed them. Gordon Cullen wrote an influential book in 1961 that introduced his ideas on urban design as storytelling, or at least, the planned revelation of a sequence of vistas to the people who moved through townscapes. It is an idea that has been fostered under the title of ‘landscape narratives’ to communicate messages about aspects of places (see Potteiger and Purinton, 1998).

The spectrum of writing can appear bewildering since it is not only considerable but comes from a wide range of disciplines, on top of which there are the cross-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary works. To reflect the whole picture would be well beyond the scope of an on-line posting with the style of this one. The next posting will attempt to start from scratch, as it were, in proposing some ideas about landscapes, the information they contain, and they ways in which people receive that information. Continuing the train of thought started in that discussion must lead towards the notion that environments can be designed and managed in order to communicate messages in the way that Cullen, Summerson, and Potteiger and Purinton have described.

Bibliography

Boorstin, D (1964) The Image, Harmondsworth, Penguin Books

Cosgrove, D (1984/1998 pbk) Social formation and Symbolic Landscape, Madison Wisconsin, The University of Wisconsin Press

Cosgrove, D & Daniels, S (eds)(1998) The Iconography of Landscape, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

Cullen, G (1961) Townscape, London, architectural Press

Gollege, R & Stimson, R (1997) Spatial Behaviour: A Geographic Perspective, New York, The Guilford Press

Holt-Jensen, A (1999) Geography: History and Concepts, London, Sage

Hoskins, W (1955) The Making of the English Landscape, London, Hodder & Stoughton

Ittelson, W et al (1974) An Introduction to Environmental Psychology, New York, Holt, Rinehart and Winston

Lawson, B (2001) The Language of Space, Oxford, The Architectural Press

Lee, T (1976) Psychology and the Environment, London, Methuen

Potteiger M & Purinton, J (1998) Landscape Narratives: Design Practices for Telling Stories, New York, John Wiley and Sons

Tuan, Y (1974/1990 pbk) Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes and Values

Tuan, Y (1977) Space and Place, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press

Urry, J (1990) The Tourist Gaze, London, Sage

Winchester, H, Kong, L & Dunn, K (2003) Landscapes: Ways of Imagining the World, Harlow, Pearson Educational

Zube, E (ed)(1970) Landscapes: Selected Writings of J B Jackson, Boston, Mass

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Towards Theory - Environment As Data

[Original posting on this web site: 01.01.07]

Anyone - doesn't have to be a tourist (or even a human being, come to that) - placed in a given environment will use five senses to relate to that environment. Some scientists will point to a probable sixth sense based on electrical signals - some fish have it; whether we do is not in my line of knowledge so that possibility will be omitted for the moment.

Vision is perhaps the most important sense to be used, hence the "Tourist Gaze" of John Urry (1990) mentioned in the previous posting on 31 December. We see a vast amount of detail very quickly and locate it relative to ourselves very easily, thanks to a wide arc of view and binocular vision. We can see attractive places, potential dangers, identify people with a high degree of perception about who they are and so on. Sight allows us to read their body language.

Tourist managers concentrate a lot of effort on manipulating our percpetions of their places, by making them attractive, keeping them well maintained and trying to ensure there are no hostile activities going on within them.

Sound is important. It's a bit more more difficult to locate its origins at times but it brings very rapid, strong perceptions which can be good, bad or neutral. Sound can range from a brief emanation from an otherwise inanimate object - such as the whistle of an approaching train - through longer-lasting patterns like the noise of the train as it arrives or the song of a bird. Or it could be a warning siren on a police car, or maybe the music played by a band parading. At its greatest complexity it can be in the form of spoken language of hugely varied character, according to the language used, mode of speech (face to face, by telephone or public announcement system).

Touch depends on ourselves and what we are doing. It is more a product of interactivity, or we might say, proactivity. Walking on a beach produces tactile sensations, themselves dependent on whether we have footware or not. The texture of stone, brickwork, grass, water, textiles, skin and fur depends on how contact is made (do we reach out or are we reached by something?). Interpersonal contact - shaking hands or exchanging kisses on meeting - tells us a huge amount about each other, and happens to bring in the possibility of smell and taste sensations. Tourism managers make prime use of sound from conversation to background music, or sound effects in an exhibition, or a whole panoply of sound in a stage performance.

The sense of smell is not always appreciated, yet as Marcel Proust wrote concerning those small cakes, it can be enormously evocative. Perhaps this is because we actively employ it rather less so when it imapcts it really does strike home. A person's odour, natural or artificial thanks to perfume; the scent of flowers, of new-mown grass, the sea, a farmyard -all play their parts daily in tourism. Smells can be managed - those little electrical units slowly burning special oils that help museum displays come alive are a good example: of newly baked bread in a reconstructed bakery, for example. Noxious smells which serve to warn humans of potential problems - of decay, pollution, leaking gas or dangerous liquids - have to be managed.

Taste is most important in the special environment of a restauraunt or food shop offering samples. Outdoor environments offer few examples - eating local food outdoors is not actually an encounter with the environment itself - but one that is noteworthy and well remembered is the taste of salt spray on the lips when near to the sea. That, and the cry of seagulls, is often recalled amongst the memories of seaside holidays as a source of pleasure.

Environments will contain different levels of sensation-causing items or events. A city like New York (Times Square pictured) is packed with the sources used by all five sensations (counting food in the delicatessen as part of it), especially as there are neon signs, traffic lights and video screens busily calling for our attention. At the other extreme a desert, grassland plain, snowscape or open ocean will have far fewer, although still contain a multiplicity of constantly-changing sources. In every environment the addition of people and their activities will add more sources according to their number and actions.

Tourists depend on their senses and any loss or damage caused to them require appropriate special assistance. Tourist managers always attempt to maintain better standards within their areas to give the best impression. The best managers understand the full range of senses that will be in play and how to get the best advantage from every one of them.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Towards Theory - Environmental Vectors

[Original posting on this web site: 02.01.07]

Let's think of those people in the graphic below - the previous posting. A couple of visitors in a new place - an environment which is probably new to them. You know that feeling you sometimes get when you wake up in the morning: Where am I? What day is it? If you had a really confusing dream you might be thinking - Who am I?

Of course we generally know just who we are, though it might get a bit confusing when age takes its toll and young children might not be too sure sometimes. And what about those kinds of phases in the teenage years when people say they are really "discovering who they are"? There is something in our psychologies that suggests knowing who, when and where (let along how or why) isn't quite as automatic as we might think it is.

In our home environment (OK - when we are "at home") it is so familiar that we aren't conscious of any kind of orientation - having to work out where we are and why. And yet, if you closed your eyes, could you picture exactly what your kitchen looks like, down to the order of the utensils hanging from that rack? As we actually look at them we know what they are and are happy to see where they are, without needing to think any further. On going out of the house the chances are we will be able to walk quite a way before thinking that we don't recognise our surroundings. We might hop on a bus or get in a car and travel along quite familiar routes. Yet there almost certainly will be people we haven't met before, or well-known people dressed differently, or vehicles that we don't know. There will be little combinations of acitivities - patterns of movement of the people, the cars and lorries, even the animals passing by. What about the flowers that have opened, or the trees that changed colour? And how often do you see a sky that is exactly the same today as it was yesterday? - cloud formations are in constant motion.

That couple of tourists will almost certainly be in a very different environment from the one where they live - that's what tourism is about. So for them they are having to take notice of where they are, to understand something about it (such as - where are the shops? - the beach?) and then act according to their own needs and to what the place has. If they have a slightly deeper interest they might be working out something about what the place used to be like and why it has the particular form and culture that they are finding. Even if they only want shops, bar and beach and have no interest in history or culture, they will still register the differences in their surroundings, the people and the climate which was almost certainly one of the reasons they came there.

From the earliest times onwards, travellers have used landmarks. Prominent hills, buildings and even patterns of vegetation have helped them recognise where they are and work out which way to go. Robinson Crusoe described moving round his desert island, using the position of trees, the change to open grassland and the nearness to the sea. He learnt to use all of his senses, first to survive and then to make the most of his little world. Even taste was important in coming to terms with the island, for he had to try eating some of what was growing there in order to discover sources of food.

The most sophisticated travellers used small details from the landscape to help them. Sailors could ‘read’ the colour and shape of the waves around them to work out their position and know what weather might lie ahead. Land travellers might use information such as which of the side trees moss was growing to understand their position, especially when the sun was not visible. In similar fashion the modern traveller uses tiny details as well as major features of the surroundings to understand places.

To a tourist, the recognition of being in a different place is the most important thing. After that it is essential to know whether it is the right place for whatever they want to do, and if not, how can they get to where they want to be. They need to know whether they are going to be safe, to have available the food and drink they need, good accommodation and friendly people (just like Robinson Crusoe on his island). The tourist wants to know, in short, whether this is a good place to be, whether they will enjoy this particular destination. Some obvious, major features of the place will influence that, but ultimately there are probably hundreds, thousands, if not an infinite number of things which will have a bearing on it. An example: is there a good beach? Is it big or small, overcrowded or empty, clean or dirty, steep or gently sloping, a nice colour, made up of sharp or rounded sand grains, be well drained or to have standing water – even worse, quick-sand? That is only the beach: what about the nature of the sea? The weather? The area behind the beach – the tourist will want to buy goods, stay overnight, be entertained, have places to explore, perhaps some countryside as well as the town. A visitor interested in history will want to know where the older places are, just how old they are, what happened there, why they were built or formed as they were. Landmarks, and the smaller details that are often called ‘cues’, are not just to do with place, but with time as well. Beyond history they are to do with natural history and even geology. Connected with history and with the people who live in the place they are to do with culture, society, the way people live today and how they live.

In mathematics there is the idea of the ‘vector’, a quantity with direction and magnitude. I suggest that it is useful to think of people in a particular place as using vectors to work out how they understand, and therefore use, the place. They see a landmark, perhaps a temple on a hill at a certain distance away, and use it as part of the way in which they work out where they are: it is the Acropolis and that reminds them they are in Athens, in Greece and perhaps far from home. Of course they used previous cues to tell them they had arrived in Athens; the flight in, the view from the aircraft window and cabin announcement, then the drive from the airport during which they encountered an infinite number of cues which gave them an idea of place and when they arrived in the city centre. The smells and later the tastes of the city added abundantly to their knowledge, often taken in quite subconsciously. Part of the point here, however, is that they are constantly reminded that they are living at a particular time and that the Acropolis and all the other historic buildings represent very different times, when people did things differently from the way they are done now. Everything about the temples of the Acropolis shows that, reinforced and added to by the displays in the museums, the words of the guide books and the human guides who take visitors around. Every one of these details helps the traveller understand the relation of their place on the globe but also their place in history and their relation to the past. They also are able to relate to the natural history and present day human culture of the place as they receive information about those aspects of it.

An important point needs making here. A vector in this sense would not be the cue itself, but the perception of how something is different, and in what kind of way. It is a measure of magnitude and direction, although since those qualities depend on the phenomenon being perceived (shape, sound volume, texture, pungency, saltiness etc) then the vector is also a function of the phenomenon. It is indisoluably linked to it. When we work out the values represented by a vector we are then able to relate to it. In this sense, therefore, it is not the phenomenon observed, heard etc (the 'percept') that is the vector, but the difference of position spatially, temporily, physically and culturally between it and the observer.

A vector might then be any kind of perception at any kind of level: the brightness of the daylight, the colour of a stone, the smile on a face or the beauty of a butterfly. Not all of these perceptions are positives – the broken glass and scaffolding poles in the photo above give reference to a derelict building which speaks of economic change and perhaps a depressed community. What the visitor makes of what they taken in through their senses depends upon their interpretation of it which is in turn dependent on their own experience, knowledge and opinions. Each detail – each vector – is interpreted alongside all the others as it is placed in a wider context which builds over time. People establish their relationship with what they see, hear etc, by putting the perceived feature into the framework of their own knowledge. They measure its position and importance (“direction and magnitude”) in relation to themselves in the world. People are constantly receiving environmental data through all of their senses and interpreting it in order to survive, use and enjoy their worlds.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Towards Theory - Environmental Data Levels

[Original posting on this web site: 03.01.06]

It helps to understand peoples' reactions to places, and therefore to be able to provide useful services or management, to be aware that different environments represent different levels of data. It might be very difficult for someone used to open grassland country to cope in the big city. It's easy to understand the noise and sense of rushing and perhaps the claustrophobic effect of high buildings close together, but there is more to it than that. The brain is trying to process enormous amounts of information coming in through five sensory channels - sight, sound, touch, smell, taste - at high speed. The competition for attention of all these messages might mean that some get forgotten or ignored even though they are important. Warning lights might be missed and accidents caused. Expensive neon-sign or video adverts might be lost amongst the tidal wave of information sweeping over people. Planners have long known about the need for variety in townscape design and the introduction of soft landscaping like quiet, green parks. The communicators who work with cities have to know how to handle the noise and razzamataz and be able to draw on appropriate other media or quiet phases as well. Effective communication depends on knowing the audience's needs and people are not all the same: tour guides, teachers, advertisers and city managers all need to know what is best practice in communication. Yet poor road signage, ineffective advertising, wasted teaching time and inadequate tour guiding are all easy to find in every city.

The opposite can also be true. The big city resident gets out in the plains, the desert or close to the sea and finds nothing - literally, since they are used to entertainment and information being in their face and the apparent lack of interesting scenery is often a cause of disappointment. They need to look closer, differently, and to learn to appreciate that what seems to be emptiness is in fact a source of huge interest. The sweep and shading of desert dunes, the great contrast with cityscapes of open grassland, the movement and colouring of lakes and seas is a source of reward to those who understand. Within those places life and activity occurs on a different scale and in unfamiliar ways. Visitors need to look for it; local people can help them find it. It's a failure if visitors go away disappointed and unaware of what these places offer, and the destination manager might just possibly be the one to blame.

Illustrated are six examples of environments with varying levels of data of the kind these current postings are discussing. There aren't absolute boundaries separating one from another - variations from place to place and within places occur quickly; also, opinions will vary as to the amount of data to be found in each, not least because it partly depends on the knowledge and experience of both visitors and managers. In addition, changeable weather or storms add large amounts of activity to an otherwise quiet place, as do the activities of human beings or wild life. A downpour of rain in a desert might quickly bring fresh growth of plants and attract wildlife, bringing more action and increasing the flow of perceptions to the visitor's brain. A desert might be cosnidered at level 1 normally but temporary activity of these kinds, while not turning it into a permanent level 2, ought to be designated as different for a spell, so would be described as level 1+ for the duration. Really heavy activity might be termed level 1++. Similar designations could be given to the others as appropriate, though it would be less useful thinking of level 5 (city, heavily built up) and level 6 (the same with many townscape media features permanently on show - adverts, signals etc) because high rates of human activity are part of their normal character.

In summary, it is important to be familiar with what it is within different environments that make people react to them as they do. That helps managers and opinion formers to know more about the communications context of their work. From that they can plan more effective strategies.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Towards Theory - Vector Sets

[Original posting on this web site: 04.01.07]

The suggestion being advanced in this group of postings is that all perceptions (or 'percepts') can be termed 'vectors' because they enable us to recognise certain features or qualities established in a definable, or measurable way.

Take a leaf, for example. Its colour might be called one vector; its texture another, its shape a third, its size a fourth, and so on. The set of vectors will tell us it is a leaf and not a blade of grass or a twig (or for that matter a person or building). It will also tell us that it is one sort of leaf - perhaps an oak leaf - and not another, and that it is seen it its spring or autumn colours as appropriate.

If we see the leaf as part of a group on a twig, perhaps with acorns, helping to confirm its nature as from an oak tree, not an elm, ash etc, we would be seeing the leaf as a set of vectors subordinate to a larger set - the twig/leaves/acorns set. The leaf is a subset of a larger group we can call a superset. Of course the twig/leaves/acorns set is also part of another superset - one further up the scale of magnitude, which we know of as an oak tree. the tree is probably part of a bigger group yet again which we call a wood. It is an infinite scale running upwards. Every group is part of a larger, superset, which is in turn a subset of an even larger superset.

In the example shown in the photos above, the basic information - the lowest order of subset - turns out to be part of a superest which consists of timberframe wall with windows within it built on a course of stonework. This group is actually a subset of one corner of a house - the next superset up the scale. That set is a subset of a house, which is in turn a subset of a residence in the setting of some grounds. The subset/superset relation could be continued higher up the scale to see it within a town park set within a valley which is within an area of Pennine hills - and so on.

It's important to recognise that sets are not fixed and are largely inventions in the mind of the observer, and they are even then only rather general concepts adopted by humans in order to understand and communicate. People use the term 'leaf' and know roughly what they mean, without having (or even attempting) to worry about an exact definition based on all of its parts. And yet people do need an understanding of what qualities make up the object known as a 'leaf'.

If a metalworker came along and reproduced a leaf of the exact shape, size and colouring of a leaf, but in metal, we would not be fooled into mistaking it for the real thing - there are several differences giving the show away - but we would appreciate that a craftsperson had produced a representation of one object by exchanging one or two basic properties - metal substituted for organic material with small changes in texture, feel etc.

In perceiving objects, we first of all tend to observe the overall features before looking closer and closer. The depth of our analysis depends not only on how much detail we need to know but on our knowledge and experience (and persistence). The building shown here is seen to be a late medieval building with later changes and additions (such as the Victorian tower). Specialists would examine the detail of the garden, trees and indeed the building itself in order to understand more and more of what is in the picture.

The visual example discussed here is based on only one of the five human senses. Were we stood in front of the house we would have the sounds of birds, the breeze in the trees, perhaps some people nearby; plus the feel of the warm sun, soft wind, springy truf or hard pavement; maybe a smell or two and in theory some taste - but as humans we use those two much less. The dog we are taking for a walk would have a better idea (interpreted differently) about the range of odours and possibly a taste or two, but be less interested in the same sights and sounds that take our attention.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Holodyne: The Action Cycle

[Original posting on this web site: 02.03.07]

What is tourism?

Tourism is a way of discovering the world: its places and people.

Tourism is a form of travel. There are four types of travel, though the traveller might simultaneously mix these four in different proportions. The four are exploration, conquest, business and tourism. Exploration might be that of the first traveller ever to step foot in a place, or it might be that of anyone visiting a place they have not seen before even though many others have. Conquest can be military, ideological or economic. Business can be to do with trade and commerce or any form of employment or occupation - merchants, teachers, charity workers etc. A journalist investigating a story might be exploring and on business at the same time, then in the evening becomes a leisure traveller enjoying the entertainment on offer. A soldier might be using force to win a battle - that is not well defined as business which is a peaceful activity - but then spend time in rest and recuperation as a tourist.

These forms of travel - tourism being one - bring the traveller into contact with new places and people and lead to a myriad instances of discovery. Discovery comes through other means, however, as well.

People have four ways of discovering their world. Babies discover it through personal contact, with parents and other humans, and also with the immediate surroundings of their clothing, cot, and room. This circle of contact is with them from their first day to their last. It can be extended by travelling, at first in a parent's arms, then a baby buggy, next a car or other form of transport. For them, the age of travelling had begun, and they start as leisure travellers: tourists.

Next encountered as their circle of contact enlarges to take in the TV set, the radio, music player and computer station, followed by books, newspapers and journals, but also photos and graphics on consumer goods, postcards and reproductions of paintings, are the mass media. While not strictly forms of mass media themselves this group can include family photos, letters and phone calls, all of which depend on communications media but which work one-to-one.

Last encountered, and first relinquished, is formal education. Through the stages from primary to tertiary and possibly continuing education, the student undergoes a mode of discovery which works in a very special way, but which also is notable for incorporating at various times all of the previous three modes. Indeed, each mode draws on the activities of the previous one. So travelling extends, and incorporates, the circle of personal contact. The mass media use reporters and correspondents who travel and make new contacts on behalf of their audience of users but then employ their particular medium in order to communicate. Educators use every mode, and, of course, the learner does the same when they use educational systems in order to educate themelves.

The next three phases follow on. 'Interpretation' is that which includes the actions which help us decide the meaning and significance of the discoveries made in the first phase. We are influenced by a range of factors (the broad headings for which are shown) such as our own physiology, psychology, knowledge and culture. For example, if we are hungry the discovery of a shop selling food will have a different significance than if we had only just exited a nearby restaurant. The influence of the people and cultural frameworks (philosophers, politicians, our family and social groups) is very important.

The next phase is that in which we take decisions. This might be a process within our own mind or it might involve informal or formal activities. It might require a family discussion or a fixed-procedure meeting. These again depend on cultures and systems but what is key to this phase is the process rather than the framework.

Finally, in the fourth phase, we take action. It can involve any of a number of possibilities, the nature of which is hinted at by the sub-heading shown. The outcome will, one way or another, lead to further discoveries, and so the cycle continues.

Of course real life is not so prescriptive as this model suggests. There are overlaps, simultaneous activities and great variation in the time taken by each phase - and indeed the speed by which it all happens. The model is trying to suggest the important elements and to point towards the complexities which exist.

*

An early academic discussion of this idea, in which the model was presented as a spiral in order to incorporate the time element, can be found in a conference paper delivered in 1988 and published shortly afterwards:

Machin, A (1989) The Social Helix: Visitor Interpretation As A Toool For Social Development, London, Belhaven

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

|