Leaders Into The Field

These postings originally appeared in the January and February 2009 blog pages. Here they are in approximate chronological order starting at the top.

.

This series of postings is about people in who have helped persuade others to explore the world for themselves.

So it will not be about the primary explorers, the original pioneers, but about those who inspired more ordinary folk to explore. It will be an eclectic mix from writers like Rousseau to TV presenters like David Attenborough.

It won't be comprehensive - how could it be with such a wide field? It won't attempt to provide more than a glimpse of their lives and work: there are plenty of published, detailed studies of each of them. The purpose of these postings is merely to draw together some of the main figures of importance to the development of tourism as education. Several of them were nothing to do with tourism as it is now known, but all of them had an influence on it. Tourism as education has its theories and its practices, even if these have yet to be codified in any form. These people have shaped some of them.

.

Richard Hakluyt (1552 or 1553 - 1616) was an ordained priest holding important positions in Tudor England which allowed him to influence national affairs. He did this through the contacts he held and the books that he wrote. Among his achievements, albeit in collaboration with others, were the founding of English colonies in Virginia and the gorwing interest in world exploration, largely for political and economic reasons.

Hakluyt became chaplain and secretary to Sir Edward Stafford, the English ambassador to the French court, enjoying the patronage of the Stafford family until his death. He also became personal chaplain to Sir Robert Cecil, who opened up important posts for him at Westminster Abbey.

His early education had been at Westminster School. His parents had both died when Richard was young so he was given a guardian, his cousin who was also named Richard Hakluyt. On a visit to his guardian he was shown "certain bookes of cosmographie, an universall mappe and the Bible" which inspired an interest in acquiring knowledge, especially of exploration. At Oxford Hakluyt read voraciously amongst manuscripts and printed works on voyages and discoveries.

His first book was a translation of a French account by Jacques Cartier of that explorer's second visit to Canada, although some confusion as to publication dates might mean that it was a book by Hakluyt himself which appeared first. This was 'Divers Voyages Touching the Discovery of America and the Lands Adjacent to the Same' which appeared in 1582. Several other books would follow. He used his contacts to meet and interview sea captains, merchants and other mariners, 'making diligent inquirie of such things as might yield any light unto our westerne discoverie in America'. Time spent with the english ambassador in Paris was partly used to collect information about the Spanish and French activities in that direction. Further books appeared over the years about voyages and the values of overseas possessions. Exploration and later, empire, would prove to have been stimulated by Richard Hakluyt, and his promotion of the colonisation of Virginia and the trading of the East India Company helped turn that interest in geography into national economic growth.

A tradition of discovery through travelling was, thanks to his books, the lasting legacy of this Tudor churchman and scholar. The Hakluyt Society, which was formed in 1846 for printing accounts of voyages and world travelling still publishes material each year today.

Richard Lassels

The term "Grand Tour" was first used by the French - 'le grand tour' - and then introduced into English usage by Richard Lassels. He wrote a book called "The Voyage of Italy" (sometimes refered to as "An Italian Voyage") in 1670. The word 'tourist' stemmed from it but was not used until the early nineteenth century.

Lassels was only one of a number of writers about the Grand Tour but it seems to have been his book which stimulated much of the early travellers in the seventeenth century - when the practice was already a century or so old but with much smaller numbers of travellers.

Richard Lassels listed four benefits that English partakers would gain: those of the intellectual, the social, the ethical or moral, and the political. He was actually writing about two established, but more localised, tours - the French grand tour and the Italian Giro. What emerged was a tour with a fairly common set of destinations even though individuals (accompanied by a tutor) were making their own way where they thought fit. The route would take in Calais, the Loire valley, Paris, Geneva (or, taking a different route, the Rhone valley to Avignon) and across into Italy for Venice, Florence and Rome. A frequent return leg went north into modern Austria and Germany and then west towards Amsterdam and then back to the UK. Some tour-makers went the opposite way round, but whichever way they travelled Rome was the high point of the journey, which could be spread over two, three or more years. Lassels was a writer who really led hundreds, if not thousands, out into the field of European society for the good of their education.

John Locke was an English philosopher who influenced many thinkers and writers in the seventeenth century when he lived (1632-1704), and subsequently many others such as Rousseau, Voltaire and David Hume. For these postings on education out of the classroom and, informally, through travel and tourism, his importance lies in his essays "An Essay On Human Understanding" and "Some Thoughts Concerning Education". Unlike his contemporaries in the church he believed human beings started life without inborn knowledge - like a 'tabula rasa' or blank page - on which knowledge gained in life would be inscribed.

In "An Essay Concerning Human Understanding" he wrote that knowledge came from external sources, which to us would mean our general environment with its stores of information and the wider world to be explored. His style is that of a man writing about philosophy in 1690. Here is an example:

"The notice we have by our senses of the existing of things without us, though it be not altogether so certain as our intuitive knowledge, or the deductions of our reason employed about the clear abstract ideas of our own minds; yet it is an assurance that deserves the name of knowledge. If we persuade ourselves that our faculties act and inform us right concerning the existence of those objects that affect them, it cannot pass for an ill-grounded confidence: for I think nobody can, in earnest, be so sceptical as to be uncertain of the existence of those things which he sees and feels".

In "Some Thoughts Conerning Education" Locke develops the idea that learning must not be a matter of absorbing facts by rote, but one of aquiring skills which can be used to learn, and that the whole process must be enjoyable in order to succeed. He writes of many things including the curriculum for learning by skills acquisition. As just one example he describes the usefulness of drawing:

"When he can write well and quick, I think it may be convenient not only to continue the exercise of his hand in writing, but also to improve the use of it farther in drawing; a thing very useful to a gentleman in several occasions; but especially if he travel, as that which helps a man often to express, in a few lines well put together, what a whole sheet of paper in writing would not be able to represent and make intelligible. How many buildings may a man see, how many machines and habits meet with, the ideas whereof would be easily retain’d and communicated by a little skill in drawing; which being committed to words, are in danger to be lost, or at best but ill retained in the most exact descriptions?"

The connection with being educated away from home and possibly out of doors is made. People were already making the Grand Tour of Europe from Britain and Locke's comments helped to encourage sketching and painting as a way of recording what the traveller encountered (see the entry on Tourist Photography in the blog posting on this web site for 30 October).

.

Locke, J (1690) An Essay On Human Understanding: available online from www.gutenberg.org

Locke, J (1693) Some Thoughts Concerning Education: avaiulable online at www.bartleby.com

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was born in Geneva in 1712 and died in France in 1778. He was an important philosopher, writer and composer who has exerted a great influence on world life and culture. His writings certainly contributed to the development of political ideologies of all shades of opinion. His ideas on education have had a profound effect on both theory and practice at all levels, even though some aspects of them were quickly rejected as being impractical. Some years after his death he was reburied in the French Pantheon in Paris as a national hero.

For someone considered to have added much to the ideas about educating children it is ironic that Rousseau had five and sent them to an orphanage where they might not have survived to adulthood. His defence was apparantly that they would have done better there as he would have been a poor father. Since orphanages had high mortality rates that view must have been questionable at the very least.

Rousseau's thoughts about education were set out in his book 'Emile', a semi-fictitious account in which the author brings up a young boy in the countryside. To Rousseau the city is a place where children would learn bad habits, mental as well as physical. Emile has a tutor who teaches him on a one-to-one basis reminiscent of those tutors who accompanied young men of wealth on the Grand Tour. The boy is educated through three stages of life. The first is up to the age of twelve when complex thinking was thought to be impossible and the child behaved according to animal instincts. From 12 to 16 reasoning begins to develop. From 16 upwards adulthood is achieved and useful skills like carpentry are acquired. Working with wood demanded skill and creativity but would not compromise the child's morals.

Rousseau thought that Nature was a good and effective teacher. He wrote "Nature exercises children continually, it hardens their temperament by all kinds of difficulties, it teaches them early the meaning of pain and sorrow".

In another section he wrote: "Men are devoured by our towns. In a few generations the race dies out or becomes degenerate; it needs renewal, and it is always renewed from the country. Send your children to renew themselves, so to speak, send them to regain in the open fields the strength lost in the foul air of our crowded cities. Women hurry home that their children may be born in the town; they ought to do just the opposite, especially those who mean to nurse their own children. They would lose less than they think, and in more natural surroundings the pleasures associated by nature with maternal duties would soon destroy the taste for other delights".

It was through this kind of idea that Rousseau became an inspiration for education outside the

town or city, or if the child were country-born it was about learning about himself or herself and their relationship to society.

Rousseau, J-J (1782) 'Emile': quotations from the Gutenberg Project (http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/5427)

Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi was a Swiss teacher and educational reformer. He was born in Zurich in 1746 and died in Brugg, Switzerland in 1827. Like Rousseau he wrote a book on education but unlike Rousseau he was a busy teacher for many years, first in Birr, then Stans, next Burgdorf and finally Yverdon.

Pestalozzi was not so much a teacher advocating outdoor education but rather one remembered as a general educational reformer who placed the pupil at the centre of education. He once said "The role of the teacher is to teach children, not subjects". His most important book was called "How Gertrude Teaches Her Children". Pestalozzi's ideas were based on starting from the simplest steps and progressing to the more difficult. Observation was to be used, followed by conscious thought about what was observed, and finally the use of speech to discuss the results within a general system of knowledge. Measuring drawing, writing, numbering and reckoning would come after that. At the heart of observation was the idea of 'Anschauung' which could be translated as 'sense impression', the 'experience' which resulted from the observation. This concept would be a key element in German, as well as Swiss, ideas about travel.

'Doing' leads to 'knowing' said Pestalozzi, so it can be said that Anschauung contained within it an active process on the part of the observer - it was not a simple, passive procedure. Seeing, hearing, touching etc had to be thoroughly performed, multiple activities, such as looking at a thing from different points of view. The knolwedge gained had to be related to other knowledge so that an integrated picture would emerge like (as we might see it) the growing completion of a jig-saw puzzle.

Children helped each other in Pestalozzi's class. He said "I put a capable child between two less capable ones. He embraced them with both arms, he told them what he knew and they learned to repeat after him what they knew not".

His experience in the early days at Stans, where he was teaching orphans gathered together after suffering during the French invasion of 1798, was crucial. Of this he said

"I learned, as never before, the relation of the first steps in every kind of knowledge to its complete outline; and I felt, as never before, the immeasurable gaps that would bear witness in every succeeding stage of knowledge, to confusion and want of perfection on these points. The result of attending to this prefecting of the early stages far outran my expectations. It quickly developed in the children a consciousness of hitherto unknown power, and particularly a general sense of beauty and order. They felt their own power, and the tediousness of the ordinary school-tone vanished like a ghost from my rooms. They wishes, tried and persevered, succeeded, and they laughed. Their tone was not that of learners, it was the tone of unknown powers awakened from sleep; of a heart and mind exalted with the feeling of what these powers could and would lead them to do".

So Pestalozzi was describing classroom teaching, but those principles that he was identifying would become the basis of out-of-the-classroom education as well. A later posting in this series will describe the writings of Freeman Tilden in 1957 about heritage interpretation in American National Parks. Tilden's principles of interpretation owed much to the ideas formulated by Pestalozzi, as did many of the ideas of educationalists in the years between.

Pestalozzi, J H (1801) How Gertrude Teaches Her Children: available online from the Internet Archive.org edition.

Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) was a German naturalist and explorer who was an early pioneer in the growth of interest in travel amongst Germanic peoples. Along with men like Carl Ritter he encouraged through his explorations and writings the German love of discovery. His modern-day countrymen and women are amongst the great travellers of Europe, making expeditions across many continents in order to experience places and peoples and to learn about the world in general. German schools have a long tradition of excursions and holidays with the same aims, well before most other countries including the United Kingdom. This is partly due to Humboldt.

His early travelling included England, Vienna and a tour of Switzerland and Italy studying the botany of those places. Then he spent five years in Latin America between 1799 and 1804, observing and describing the countries he saw in a new, scientific manner. His account of the travels were published over 21 years in a monumental set of books. It was Humboldt who first suggested that South America and Africa were once joined, long before the Atlantic Ocean was formed. In 1845 towards the end of his life he wrote the five volumes of his work 'Kosmos' which set out to draw together different areas of scientific knowledge. Darwin, Goethe, Jefferson and many others regarded him as one of the most prominent of scientists. Humboldt inspired later generations to travel and explore like he did - even if they were to use more comfortable means of touring to do so.

The importance of German efforts within geography is shown by Carl Ritter (1779-1859) who was a close contemporary of his fellow countryman, Alexander von Humboldt.

Ritter was not an explorer of new lands, however. He was a collector of knowledge through constant with men who did travel. What he did do outside the classroom and lecture hall, however, was to be a propagandist against slavery and racism. He corresponded with the Royal Geographical Society in London, who were mainly interested in exploration to further the economic gains of Britain. He had taught Heinrich Barth who explored northern and western Africa and who worked on behalf of the British government to eradicate slaving.

Carl Ritter began to publish his great series of books called 'The Science of the Earth in Relation to Nature and the History of Mankind' in his earliest days as a teacher. It reached 19 volumes but by the time of his death it had covered only Asia and his particular interest, Africa.It was Ritter who promulgated the view that geography was a kind of comparative anatomy of the world, and that its mountains, deserts, glaciers and river valleys were instrumental in shaping the history of mankind. "The earth is a cosmic individual with a particular organisation, an 'ens sui generis' with a progressive development: the exploration of this individuality of the earth is the task of geogarphy" he wrote. Ritter was casting the shape of geographical thinking for the next several decades.

Adam Sedgwick (1785-1873) was born in Dent, Yorkshire, and attended the nearby Sedbergh School. After becoming a student at Trinity College, Cambridge he took holy orders, in 1817, but the following year moved on from being a Fellow of Trinity College to becoming the Woodwardian Professor of Geology in the University of Cambridge. "Hitherto I have never turned a stone" he is reputed to have said on his appointment, "henceforth I shall leave no stone unturned".

Sedgwick's importance in the general area of education out of the classroom was in the field excursions he organised for his students and other interested people. In these he inspired many - including women, who he allowed in to his classroom lectures, unusual for the time - to take an interest in exploring the countryside. He wasn't the first to lead geological excursions, William Buckland of Oxford having done so in 1832, Sedgwick following in 1835. The Cambridge professor's trips into the Fens were immensely popular, however, with sometimes up to 70 students following him on horseback in order to hear five lectures in a day.

Adam Sedgwick was also influential in choosing the young Charles Darwin as a field assistant. Darwin studied geology after achieving his first degree. When he made his famous voyage in HMS Beagle he sent rocks and fossils from South America back to Sedgwick and kept up a correspondence with him. They were to disagree on the matter of religion and evolution but the fact remains that Sedgwick had contributed to Darwin's exploration skills and scientific knowledge just as he had with many other people. The study of geology in the field was some way ahead in Britain of that of geography and Sedgwick was one of the reasons why.

Thomas Cook (1808-92) is today considered to be the founder of one of the world's most successful travel agencies. And so he was. But that was not what he set out to do, and it in a way places him in too modern a context when he was a really part of the religious fervour of the early nineteenth century. Britain was fast becoming industrialised; factories, railways and cities were changing the landscape. Damaging social conditions had been created through overcrowded housing, pollution and harsh industrial conditions. Poverty, crime and drunkeness were often the result.

Cook was a cabinet maker. He published Baptist leaflets and in 1828 became a Baptist minister in Melbourne, Derbyshire. As one of a movement who campaigned for temperence in drinking habits - usually by giving up alcohol entirely - he preached against the evils that resulted and published leaflets to support the efforts of his fellow campaigners.

The flash of inspiration which was to change his life came while travelling by road in Leicestershire, but thinking about the railways which were being built around the country. Cook was a preacher, a publisher and a propagandist. His aim is life was evangelical - to unite man with man, and man with God. He and others believed the way to God lay along a path of good human behaviour, and that meant among other things giving up the alcohol, the cause of drunkeness, violence and other antisocial problems. Cook knew that communicating these ideas would be easier and more effective on a large scale if those he wished to have in his audience when preaching were feeling at their most receptive and positive. It would be good to take the people away from their normal surroundings full of industry and toil and put them somewhere more pleasant, let them relax and enjoy good fellowship, perhaps play some healthy games - even to have a decent picnic provided. There could be music provded by a brass band, some hymn-singing of the sort they enjoyed in church and chapel. What a marvellous thing it would be if they were not only entertained by food and play but perhaps excited by something new, something exciting, spectacular even.....

The railway could supply some of the answers to the main needs that he was seeing. On 5 July 1841 the event he had begun to shape that day out in the countryside took place. It was also the event that would launch a whole new set of activities and the employment which went with them: mass travel, tour operations and - the heart of what Thomas Cook was seeking - travel as education.

On that day he had hired a train from the Midland Counties Railway to take 570 passengers from Leicester to Loughborough at a cost of one shilling (5p) per person. In a field in the town the crowd had food, non-alcoholic drink, music and games - and speeches on the joys of temperance. The excitement of having made an eleven-mile journey in the open wagons of a train

must have been immense. The day was judged a success all round, so much so that Cook made further excursions over the next few summers for temperance groups and Sunday-school pupils. In 1845 he took a party to Liverpool, booking evrything needed at an all-in price and offering trips by sea along the north Wales coast. Information booklets about the journey and the destination were circulated to evryone. In 1846 he escorted 350 people from Leicester to Scotland. In 1851 he ran a number of trains carrying 165,000 visitors to the Great Exhibition in London. There were failures - a bankruptcy which had to be overcome - but persistence established Thomas Cook as the pioneer that we know of today - a pioneer of tourism as education whose business would take people across continents and exploring around the world.

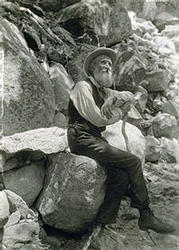

John Muir (1838-1914) was one of the most important naturalists in the USA during the nineteenth century. His influence is still great through the Sierra Club which he founded and the books that he wrote. His love of the natural world and his efforts at arousing knowledge and concern for it have made him a key figure in education as well as travel. The modern environmental movement, which is usually seen as a product of the 1960s, has to acknowledge him as one of its forerunners.

Muir was Scottish by birth and from a large family which moved to Wisconsin in 1849. Inspired by a fellow student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who talked about the relationship of wild flowers to garden vegetables, John Muir became a self-confessed enthusiast for the natural world. He withdrew from his course after several years of part-time study and walked from Indiana to Florida. His plan had been to go on to South America but illness forced him to abandon the idea and he turned to California instead. Once there Muir took himself to the Yosemite Valley, a place which overawed him. “No temple made with hands can compare with Yosemite, the grandest of all special temples of nature”, he later wrote.

After a number of jobs John Muir became a shepherd in the Yosemite area, taking up climbing and hiking to explore the wilderness. He moved to become the manager of a sawmill, building a cabin on Yosemite Creek. It was during these early days that he began to develop ideas of how this landscape had been formed – in his view, glaciers has sculpted many of the features. It was an opinion which clashed with that of Josiah Whitney, head of the California Geological Survey, who, like many geologists of his day thought that a catastrophic earthquake had formed the Yosemite scenery as it now appeared. Over time it was Muir’s interpretation that gained acceptance and his ideas were published int the first of many writings in papers and books.

Having married into a family owning a large ranch in Martinez, the shepherd turned mill manager now became the manager of orchards and vineyards on the ranch. His travels, explorations and writing increased with several books to his credit which have since been read by millions of people. Prominent Americans like Ralph Waldo Emerson, railroad president E H Harriman and President Theodore Roosevelt travelled to meet him and spending time walking in the mountains or travelling by ship along the north-west coast. Through such meetings he was able to convince national figures of the need for federal control of the Yosemite wilderness areas through the system of national parks. The Sierra Club, which now has millions of members, was founded by John Muir to campaign for conservation and education in matters to do with the environment. His books, like ‘The Mountains Of California’ and ‘My First Summer In The Sierra’ stand alongside the Sierra Club and the creation of Yosemite as a national park as memorials to a remarkable pioneer.

John Bartholomew (1860-1920) was the third of four men of that name, his grandfather, father and son all being known that way. His grandfather founded a map-making business in Edinburgh that would become famous and still exists. His father continued the work, he did himself – with even greater success – and his son did, too.

This John Bartholomew introduced street maps of large cities, maps for the railway timetables and maps for car owners. He introduced special ways of helping users to see the shape of hills and mountains by adding coloured contour-layers to the map. There were specialist atlases, too – for meteorology and zoogeography. The first Times Atlas of the World was his work, though first published posthumously, in conjunction with the newspaper. It still continues.

His importance lies not only in this work, however, but also in his related interests and activities. He began to work for his father’s business in 1880 and four years later was the co-founder of the Scottish Geographical Society, becoming its secretary, a post he held until his death. 1888 saw him elected to the Royal Geographical Society in London; four years after that he became secretary of one of the sections of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. King George V appointed him Cartographer Royal in 1910.

While the Ordnance Survey remained the national surveyor during his lifetime, it was Bartholomew who used the marketing of maps in such a way as to popularise their use and encourage travelling, before the OS itself put effort into making its own maps more readily available by selling them through bookshops in attractive covers that appealed to the walker, cyclist and car owner.

|